SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Vehicle: | 1973 Alpine A110 |

| Years Produced: | 1963–77 |

| Number Produced: | 7,500 (approximate) SCM Median Value: $168,000 (1600 VS) |

| Chassis Number Location: | Frame in engine compartment |

| Engine Number Location: | Side of block, under carburetors |

| Club Info: | Club Alpine Renault |

| Website: | http://www.clubalpinerenault.org.uk |

| Alternatives: | 1960–68 Mini Cooper, 1963–76 Lancia Fulvia, 1966–73 Porsche 911 |

| Investment Grade: | B (1600 VS) |

This car, Lot 37, sold for $304,985 (€262,240), including buyer’s premium, at the Artcurial Paris auction on October 24, 2021.

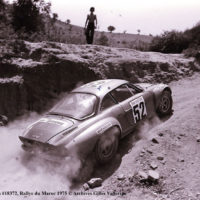

Over the past 70 years, world-class rally cars have come in a variety of guises, from the barely-improved-from-street-specification sports and touring cars of the 1950s and ’60s to the insane, overpowered, all-wheel-drive Group B death-wish cars of the ’80s. Though each has its own set of endearing characteristics, for those of us “of a certain age,” the rally cars of the mid-1970s are the most attractive. They are fabulous fun, beautiful and exciting to drive, but still fundamentally racing sports cars that can be enjoyed without worrying about your organ-donor card being current.

From a garage in Dieppe…

Let’s do some background. Jean Rédélé, a young Renault dealership owner from the English Channel port of Dieppe, France, started racing Renault 4CVs in the early ’50s. He ended up building his own hot-rod parts for Renaults, and in 1955, he formed the Alpine company (unrelated to Sunbeam) to build his own cars. Based on Renault platforms with fiberglass bodies, Alpines quickly became the sporting side of Renault. The first was based on the 4CV, and later the Dauphine mechanicals, though now with a stiff tubular backbone chassis, named the 108.

When Renault introduced the new R8 saloon in 1962, Alpine was already redesigning the 108 to accommodate the new, larger mechanical package, and in 1963 the A110 was introduced. The A110 proved to be Alpine’s most successful car by far, with roughly 7,500 produced between 1963 and 1974. There were, of course, substantial mechanical changes over the years, as Renault produced newer, bigger and more-sophisticated components to use, but the basic look of the A110 remained constant.

Like a French Lotus

By the late ’60s, Alpine had become Renault’s de facto performance and competition department, with 100% of Renault’s competition budget going to Alpine. In 1971, Renault bought the company outright, so the later Alpine 110s are pure Renaults. Alpine’s primary emphasis was on European rallying, particularly winter rallies like Coupe des Alpes and Monte Carlo. It was there, in the mountains and snow, that the rear-engine A110s were a formidable competitor. Wonderfully balanced, if arguably underpowered, the Alpines were at their best when the conditions were awful.

In honesty, calling them underpowered isn’t really fair. As anyone conversant in newer supercars can attest, there are two approaches to going fast: big and heavy with lots of tire and horsepower, or small and light with less grunt but more balance. Alpine was more the French Lotus, its cars small, light and flickable above all else.

The A110 was notoriously tiny. SCM Senior Editor Rory Jurnecka jokes about being unable to get both himself and a passenger inside. [Only half-joking! — Ed.] Two scrawny racers, maybe, but only one full-size American. In rally trim, the A110 weighed about 1,350 pounds and the R16-based alloy 1600 made roughly 155 horsepower (the fire-breathing 1800, appropriately more), so power-to-weight stood easily against larger competition.

From a golden era

As mentioned, the 110 was introduced in 1963 and the basic form didn’t change much, but the car itself evolved substantially. The glory years were from 1968 through 1973, after tuner Marc Mignotet tackled the horsepower problem with the 1,600- and 1,800-cc engines.

The culmination for Alpine (and arguably for the “gentlemen days” of rallying) was 1973, when the A110 won the inaugural World Rally Championship for manufacturers handily. In 1974, Lancia introduced the Stratos, with Ferrari’s 2.4-liter “Dino” V6 in a chassis designed from scratch as a pure rally racer, and the world changed.

From that point forward, horsepower and wild abandon ruled. Cars got exponentially faster season after season as excitement, danger and spectator appeal snowballed in a direct line to the “Killer Bs.” Much was gained but also lost, innocence and amateurism among the latter.

This leaves the late-series Alpine A110 close to the pinnacle of the nostalgic period of rallying, and this particular example is special. It was built specifically for the Morocco rally. As such, it has both the go-fast pieces and the special construction attention needed for one of the world’s toughest gravel rallies. Though originally used as a “mule” (reconnaissance) car, it saw plenty of rally use before getting put away, so it has excellent history. Now restored, it is both collectible and useable for vintage rallying. As an old rally car, it is not expected to be pristine. Rock chips, dents and scratches are part of the provenance, so playing with the car won’t hurt its value. If you break it, you can fix it without losing any investment.

A nationalistic market

While praising the Alpine 110 as a joy to use and a worthy collectible, I need to add that vintage FIA rally cars are an almost exclusively European phenomena. The Alpine rally cars are seldom found outside France. It is not a coincidence that this car (and most Alpine rally cars in the SCM Platinum database) sold at French auctions. The buyers, certainly for the valuable ones, are all French. This limits the market, but for the few really good ex-factory rally cars, it doesn’t seem to affect the value. There is plenty of money chasing them.

I will propose that the markets for vintage rally cars are more national in nature than for other racers. The English prefer their Minis, Cortinas and Escorts; the Italians tend to collect Lancias and Abarths; the Germans their Porsches and BMWs. Americans are not serious players in rally-car markets; there appears to be little interest here. That said, the markets for good rally cars are real and strong, and this car was fairly sold, most likely to a Francophile buyer. ♦

(Introductory description courtesy of Artcurial.)