The long legal battle over ownership of the #1 Briggs Cunningham 1960 Le Mans Corvette is over.

When we last wrote about this fascinating case (January 2014, p. 42), the parties were about to argue a motion to dismiss the lawsuit entirely, which was not granted.

A few weeks ago, they went to court to argue another motion about storage of the Corvette. The judge, in a surprise move, took them into his chambers and told them they should find a way to settle the case.

Just 4½ hours later, they reached a final settlement under which the Corvette is owned 30% by Kevin Mackay and 70% by the Domenico Idoni and Gino Burelli partnership, with Domenico and Idoni having 90 days to buy Mackay’s interest for $750,000.

This result is a stunner.

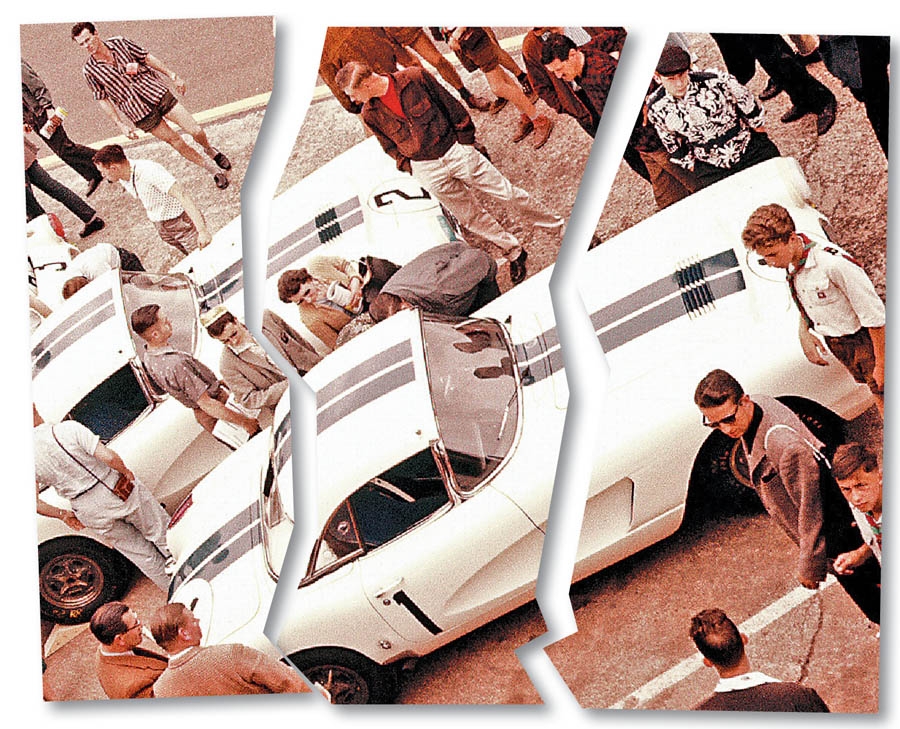

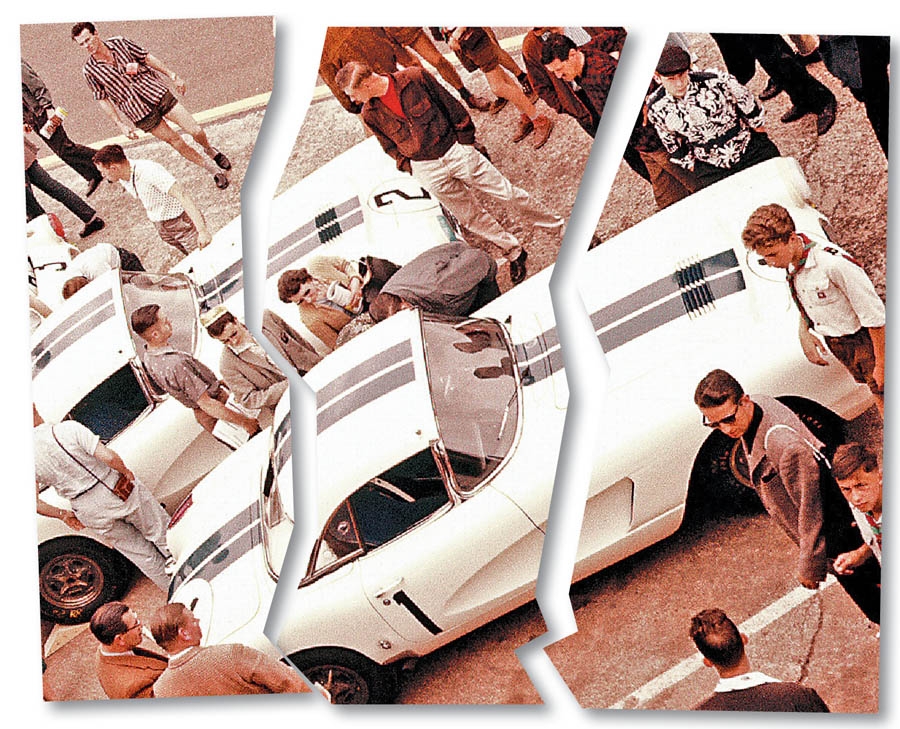

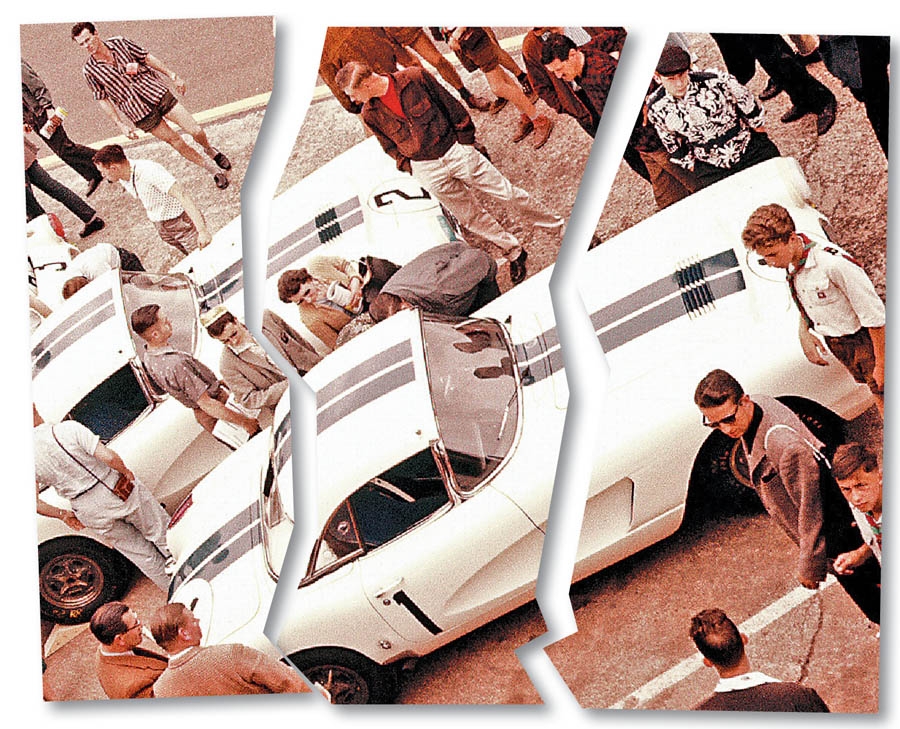

To refresh your memory, the Corvette we are talking about is the #1 car out of the group of three Corvettes the Briggs Cunningham team took to Le Mans in 1960. The car’s 8th overall and first-in-class finish made quite an impression for Chevrolet and the American automobile industry.

A long, twisty road

The #2 and #3 Le Mans cars had been located and recovered, but the #1 car was missing until 2012. It was located and acquired by Chip Miller as a favor for Kevin Mackay, who had restored #2 for him. It was purchased from the estate of Richard Carr, a Florida judge and car collector who had stored the car in his warehouse until his death.

As soon as the discovery was made public, Dan Mathis Jr. popped up and claimed that the Corvette was stolen from his father, Dan Mathis Sr., and that he was the rightful owner. Mathis had entered into a partnership with Idoni, a Corvette historian, who was acting on behalf of his partnership with Burelli. Mathis Jr. lost his interest in the claim when he filed bankruptcy and the trustee sold it to Idoni and Burelli.

The chain of title went through Jerry Moore to Mathis Sr. before it got foggy. Mackay’s version was that Mathis Sr. traded it to John Lehmkuhle, who sold it to Carr. The Mathis/Idoni/Burelli version is that the car was stolen from Mathis Sr. — perhaps by Lehmkuhle — before it went to Carr. Reconciling or just deciding between those stories was what the lawsuit was all about.

Why would Mackay settle?

“Legal Files” reasoned that, based upon what was known at the time, things looked pretty good for Mackay. Mackay is a very savvy guy, and he was well represented by the very capable Bryan Shook. Why would he take $750,000 to just walk away?

Mackay told “Legal Files” he was ready to do battle that day and was blindsided by the judge’s settlement recommendation.

The judge told them, “This is a fascinating and very complicated case with lots of twists and turns. It’s a legal jump ball that can go either way. You really should try to settle it.”

Whether it was the words, the tone of voice, the body language or the combination, Mackay says, “It put the fear in me. I was already invested over $200,000 in this. How much more would I be in it before it got resolved? And who knows which way it would turn out?”

Shook echoed that sentiment, having grown quite concerned about not being able to predict the outcome. He thought that the judge had made some rulings on preliminary motions that made it impossible to predict which way he was going to decide the case. It had become quite clear to Shook that the case was going to go all the way to trial — and perhaps even an appeal afterward. There was most likely not going to be a quick resolution.

Huge relief

Mackay is happy to have this behind him. The time and attention he had to give to the lawsuit had grown detrimental to his Corvette restoration business and was causing strain on his marriage. The settlement money wasn’t as much as it could have been, but it was a lot more than the $75,000 he paid to buy the Corvette and, after paying his attorney fees, it would leave him enough to do a couple of project Corvettes he wants to buy.

Most important, Mackay is ecstatic that all the Cunningham Corvettes are going to be back in the public eye, and he is pleased to be a part of history. He modestly notes that all the research work he has done on this car, as well as his restoration of #2, should make him the logical choice to restore #1, and he is hopeful that opportunity will come his way.

Vindication for Idoni

Idoni told “Legal Files” that he had been searching for this Corvette for 30 years. He traced it to Jerry Moore, who had purchased it from a used car dealer in Tampa, FL.

Moore was a foreman in Mathis Sr.’s pool-installation company. Mathis liked the car and unexpectedly offered him $700 for it. Moore accepted it and gave Mathis the signed-off title. Neither of them knew anything about the history of the Corvette, but they knew it was fast and had a very stiff suspension, so it had to be something special.

For some reason, Mathis never titled the car in his name, but he carried the title in the glove box in case he was stopped by police. The title disappeared with the Corvette when it was stolen.

Idoni states that Mathis’s oldest daughter, then about 21, was living with Mathis when the car was stolen. She recalls the police coming to investigate the theft. Idoni also states that Mathis was quite successful in his business and had owned a number of race cars. He didn’t sell any of them, but had all of them in his possession when he died, except, of course, for the stolen Corvette.

Additional corroboration comes from Carr’s failure to title the Corvette in his name. As a judge, Idoni figures he would have found a way to do that if it had been possible, and speculates that Carr may have known there was a problem.

Idoni believes the case would have boiled down to Lehmkuhle’s credibility, as he was supposed to have sold the car to Carr. Idoni points to Lehmkuhle’s lengthy rap sheet for car theft and says that Lehmkuhle testified on deposition, “I’ve been stealing Corvettes for 40 years, but I didn’t steal that one.”

Idoni suggests that Mackay knew he was going to lose, which explains why he settled for so little — the 30% is illusory, as the car is going to sell for much more than the $2.5 million bandied about. The $750,000 Mackay will get will be an even smaller percentage of the final value. But, to be fair, $750,000 is still a lot of money. If Mackay had so little chance of winning, why pay him that much?

Litigation realities

“Legal Files” has said many times that litigation is no picnic. This case is a great example of that. No matter how good your case seems to be, the judge or jury is always a bit of a wild card.

As Mackay said about the judge, “He didn’t seem to be a car guy. Maybe he’s a golfer.”

Odds are, not many judges are car guys, and trying to get across all the little twists and turns we all know so well about the car hobby can be a challenge. Experienced litigators will tell you that if you have a rock-solid, slam-dunk case, that means you have an 80% chance of winning. You stand to invest a lot of money in litigation expenses before that final — and often unpredictable — decision is made.

Then you have to consider the human toll. Your attorney can’t do everything without you. Litigation takes a lot of your personal time and attention, all of which is time away from your hobbies, business and family. You never get that time back.

Those reasons are why “Legal Files” previously suggested the parties should find a way to settle this, and they are likely the same reasons why the judge did the same. They are also the reasons why it is hard, even with 20-20 hindsight, to know whether a settlement was a good one or a bad one.

Looking to the future

For the rest of us, this is pretty exciting news. The last of the Cunningham Corvettes is soon going to find a new home. Hopefully, the new owner will restore it to its former glory and park it somewhere we can all see it. And, with a little luck, we’ll see all the Cunningham Le Mans Corvettes together one day. ♦

John Draneas is an attorney in Oregon. His comments are general in nature and are not intended to substitute for consultation with an attorney. He can be reached through www.draneaslaw.com.

The long legal battle over ownership of the #1 Briggs Cunningham 1960 Le Mans Corvette is over.

When we last wrote about this fascinating case (January 2014, p. 42), the parties were about to argue a motion to dismiss the lawsuit entirely, which was not granted.

A few weeks ago, they went to court to argue another motion about storage of the Corvette. The judge, in a surprise move, took them into his chambers and told them they should find a way to settle the case.

Just 4½ hours later, they reached a final settlement under which the Corvette is owned 30% by Kevin Mackay and 70% by the Domenico Idoni and Gino Burelli partnership, with Domenico and Idoni having 90 days to buy Mackay’s interest for $750,000.

This result is a stunner.

To refresh your memory, the Corvette we are talking about is the #1 car out of the group of three Corvettes the Briggs Cunningham team took to Le Mans in 1960. The car’s 8th overall and first-in-class finish made quite an impression for Chevrolet and the American automobile industry.

The long legal battle over ownership of the #1 Briggs Cunningham 1960 Le Mans Corvette is over.

When we last wrote about this fascinating case (January 2014, p. 42), the parties were about to argue a motion to dismiss the lawsuit entirely, which was not granted.

A few weeks ago, they went to court to argue another motion about storage of the Corvette. The judge, in a surprise move, took them into his chambers and told them they should find a way to settle the case.

Just 4½ hours later, they reached a final settlement under which the Corvette is owned 30% by Kevin Mackay and 70% by the Domenico Idoni and Gino Burelli partnership, with Domenico and Idoni having 90 days to buy Mackay’s interest for $750,000.

This result is a stunner.

To refresh your memory, the Corvette we are talking about is the #1 car out of the group of three Corvettes the Briggs Cunningham team took to Le Mans in 1960. The car’s 8th overall and first-in-class finish made quite an impression for Chevrolet and the American automobile industry.

The long legal battle over ownership of the #1 Briggs Cunningham 1960 Le Mans Corvette is over.

When we last wrote about this fascinating case (January 2014, p. 42), the parties were about to argue a motion to dismiss the lawsuit entirely, which was not granted.

A few weeks ago, they went to court to argue another motion about storage of the Corvette. The judge, in a surprise move, took them into his chambers and told them they should find a way to settle the case.

Just 4½ hours later, they reached a final settlement under which the Corvette is owned 30% by Kevin Mackay and 70% by the Domenico Idoni and Gino Burelli partnership, with Domenico and Idoni having 90 days to buy Mackay’s interest for $750,000.

This result is a stunner.

To refresh your memory, the Corvette we are talking about is the #1 car out of the group of three Corvettes the Briggs Cunningham team took to Le Mans in 1960. The car’s 8th overall and first-in-class finish made quite an impression for Chevrolet and the American automobile industry.

The long legal battle over ownership of the #1 Briggs Cunningham 1960 Le Mans Corvette is over.

When we last wrote about this fascinating case (January 2014, p. 42), the parties were about to argue a motion to dismiss the lawsuit entirely, which was not granted.

A few weeks ago, they went to court to argue another motion about storage of the Corvette. The judge, in a surprise move, took them into his chambers and told them they should find a way to settle the case.

Just 4½ hours later, they reached a final settlement under which the Corvette is owned 30% by Kevin Mackay and 70% by the Domenico Idoni and Gino Burelli partnership, with Domenico and Idoni having 90 days to buy Mackay’s interest for $750,000.

This result is a stunner.

To refresh your memory, the Corvette we are talking about is the #1 car out of the group of three Corvettes the Briggs Cunningham team took to Le Mans in 1960. The car’s 8th overall and first-in-class finish made quite an impression for Chevrolet and the American automobile industry.