This month’s “Legal Files” concerns a recent situation in which a friend bought a car that was listed in an online auction. Except that “Bob” didn’t win the auction; he wound up as the underbidder. The high bidder did not meet the seller’s reserve, however, and the auction was a no-sale.

Shortly after the auction ended, Bob was contacted by the seller, who asked if he was still interested in the car. Bob said that his bid was as high as he was willing to go. The seller took it. They completed the sale independently of the auction site, and the car was on its way to Bob.

He was curious about why the seller had handled the auction this way. He also didn’t think it was fair that the online auction company was cut out of its commission. Bob contacted the auction company to inquire about this and was told not to worry about it.

Since the bidding did not meet the reserve, the parties were free to do as they wished.

What’s going on?

It’s pretty hard to find a solid angle here. The online auction company charges the seller a modest listing fee. It also charges the buyer a 5% commission, capped at $5,000. The seller already paid the listing fee, so would incur no further expense with the auction regardless of outcome.

With no potential savings, why would the seller go this route and cut the auction company out of its commission? The seller could have just dropped his reserve price and taken the high bid, making it easier on himself. And actually making a little bit more on the sale, in this case, as Bob was the underbidder. We’re scratching our heads here trying to figure out what happened.

SCMers all know that the hammer price at an auction is not the full price. We have to add the buyer’s premium to the hammer price to determine how much the buyer actually paid, and that amount is what we always report in our auction reports. Buyers are keenly aware of this reality as well. They know that if they bid $80,000 on a car with a 5% buyer’s premium, they are really agreeing to pay $84,000 for the car.

Cut out

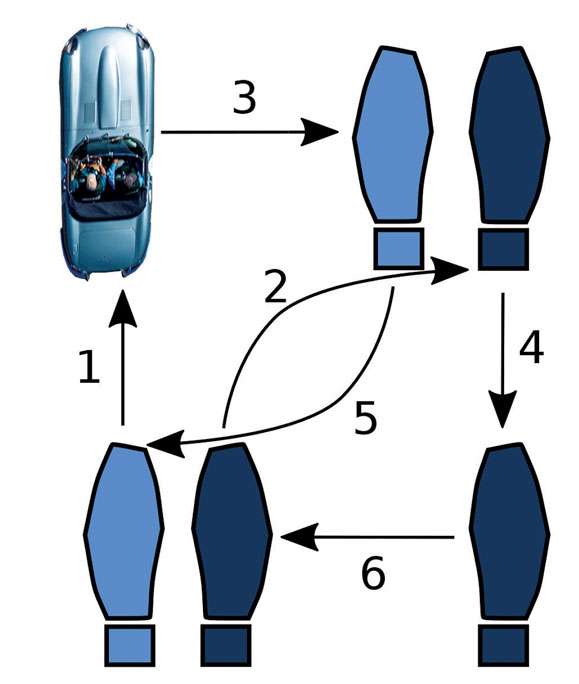

When a live, in-person auction high bid comes close to, but does not meet, the reserve, there’s always a post-hammer effort to make a deal. But now small dollars become important dollars. The seller gets more realistic about the value of the car, often with “counseling” from the auction staff. The bidder stretches to offer every dollar he can. In some cases, the auction company cuts its commissions to fill the gap and get the deal done.

When an online auction closes without the reserve being met, a savvy seller may realize that he can negotiate a better deal with the buyer because he can now pay the seller the commission that would have gone to the online auction company. So, that $80,000 bid can go up to $84,000 without costing the buyer another dollar. Basically, the seller is swiping the auction company’s commission in this scenario.

But that doesn’t seem to be what happened with Bob’s car. The high bidder did not buy the car. (Was he a real bidder?) The seller quickly came back to Bob, the underbidder, never mentioning anything about avoiding the buyer’s premium, and just took Bob’s bid. This all happened in a short period of time after the auction.

Sometimes, when you can’t figure out the angle, there isn’t any. Maybe there were other factors outside of the auction that affected the seller’s behavior.

Earning the commission

The in-person auction companies have this all figured out. Typical consignment agreements give the auction company a specified period of time after the live auction to complete a sale and earn their commission.

Part of the routine procedure in an in-person auction is that the consignor signs off on their title and leaves it with the auction company. The primary reason for that is to facilitate the title transfer after the successful auction. The title is in hand, it has been reviewed to be sure there are no issues, and it can be delivered to the buyer without delay. But that also makes it easier for the auction company to complete the post-auction sale. Without the title, it is harder for the consignor to sell the car himself.

These auction companies also protect themselves on the front end. Consignment agreements typically provide that the consignor agrees not to sell the car before the auction. That restriction is justifiable when you consider what goes into the organization of a live auction.

The auction slots are sold in advance. Catalogs are written, printed and disseminated to the registered bidders. The auction companies put a lot of money and effort into advertising and promoting the auction. Auction staff personally contact their best customers and let them know a car they may be interested in is coming up. All this costs a lot of money, and some of it gets wasted if the consignor can pull the car at the last minute.

Still, the auction company can’t exactly come and get your car out of your garage to prevent you from selling it. But selling it constitutes a breach of your contract with the auction company, and you can be held liable for damages. The damages are probably the full commission that the auction company would have earned on the sale. It’s hard to quarrel with the sale amount being equal to what you actually sold the car for, but the auction company could also try to establish that it could have achieved a higher sale price, and a correspondingly higher commission.

Consignment dealers approach the situation in much the same way. Consignment agreements typically provide that the dealer gets paid if the car sells to anyone during the term of the consignment, and also if it sells afterward to someone they dealt with. That is much the same as the in-person auction-company deal. However, the consignment dealer usually does not have the title in hand, and the consignment can usually be terminated at any time, so it’s harder to prevent the seller from making a direct sale.

But the direct sale would still be a breach of the consignment agreement, exposing the seller to the same damage claims described for the in-person auction companies.

Real-estate parallels

This situation should be quite familiar to readers. It’s much the same as an exclusive listing given to a real-estate broker. Once the listing agreement is signed, the broker gets paid their commission no matter who sells the property, the owner included. If the broker brings a full-price offer and you reject it, the broker earns their commission. If the listing expires or gets canceled, the broker still gets the commission if the property sells within a specified time to anyone with whom they had contact.

Could the online collector-car auctions do the same thing? Sure, they could try, but they would have a harder time actually making it work. Once the auction ends with the reserve unmet, the auction company has no further involvement with the transaction. It becomes difficult for them to even learn about the post-auction sale.

The online auctions aren’t in the same position as the in-person auctions. They don’t have possession of the car, nor do they ever take possession of the title. They could, of course, but that would be a fundamental change in their business model.

The online auction companies have structured their business to specifically avoid becoming an automobile dealer. Technically, all they do is bring buyers and sellers together, and the buyer and seller then negotiate a sale after the auction ends. If the online auction company took possession of the car, held the title, or injected itself into the transaction in any significant way, they would be treated as a dealer under the law, with all of the associated legal consequences and regulatory requirements.

It’s easier and more cost effective for these companies to lose a few commissions than to take on those liabilities and costs. ♦

John Draneas is an attorney in Oregon and has been SCM’s “Legal Files” columnist since 2003. His recently published book The Best of Legal Files can be purchased on our website. John can be contacted at [email protected]. His comments are general in nature and are not intended to substitute for consultation with an attorney.