Preston Tucker sure had big dreams. After World War II ended, he embarked on an ambitious plan to design, build and market his own car. His dreams came to fruition, and his eponymous company eventually produced 51 Tucker 48s before it went down in a financial firestorm.

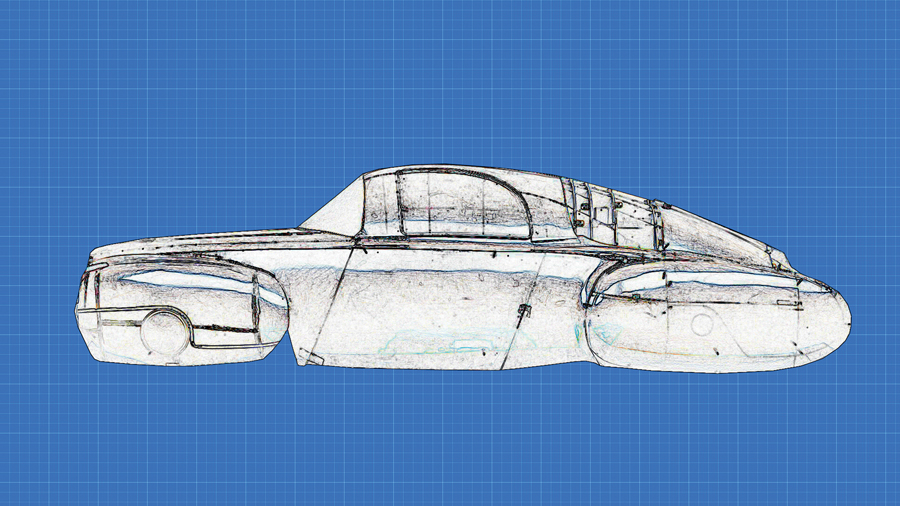

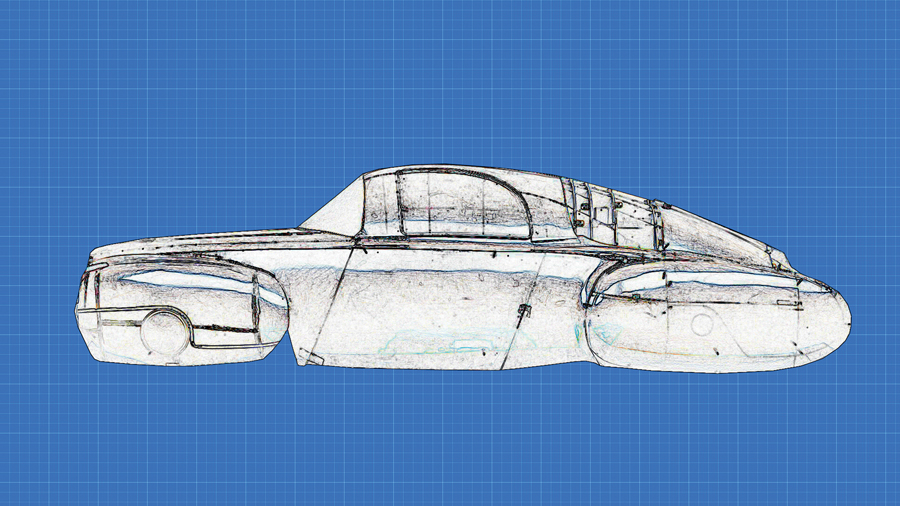

Tucker’s car was identified as the Tucker Torpedo during its design and promotion phase. When the concept was finalized and ready to go into production, Tucker reportedly grew concerned about “Torpedo” reminding people of World War II. So the model was renamed the “48,” for its year of manufacture. Thus, all Tuckers built were 48s, and no Torpedoes were actually built. However, the Torpedo name caught on, and the 48 is frequently incorrectly referred to as a Torpedo.

A bright idea

Bob Kerekes, already an owner of a Tucker 48, came up with the idea of building a Tucker Torpedo.

He contacted Robert Ida about building it. According to Kerekes, he had previously purchased two cars from Ida Automotive, liked them, and “considered them to be honorable people.”

On July 23, 2013, Kerekes and Ida entered into “an agreement to build a custom automobile, the Tucker Torpedo, which was envisioned by Preston Tucker in 1946–48 but never actually built. This was all going to be done with the sanction and participation of the Tucker family, with Sean Tucker actually doing work on the car. The full price of the building [car] was to be $800,000.” Kerekes paid $165,000 up front, and the remainder was to be paid as construction proceeded. Kerekes “envisioned this as a two-year job, with Rob Ida working on it full time.”

Slow progress

More than four years later, in late 2017, Kerekes had paid Ida a total of $675,000. This was about 85% of the agreed-upon full price, yet the Torpedo was nowhere near done.

Kerekes claims that his expert inspected the project at that time and concluded it was only 45% to 50% complete. Ida resisted his demands for a specific finish date, and eventually projected a completion date in mid-2022. Kerekes balked at that, as he would be 87 years old at the time. Plus, Ida asked for an additional $100,000 on the contract to compete the work.

Pebble Beach showing

Without any resolution of the situation, Kerekes learned earlier this year that the Torpedo had been accepted, with special dispensation, for showing at the 2018 Pebble Beach Concours. The acceptance letter expressed gratitude that the “Ida and Tucker families” were willing to display the Torpedo.

This was more than Kerekes could bear. First, he couldn’t get his car finished on schedule. Now, it was going to be finished and shown at Pebble without any mention that he was the owner.

Kerekes fired off an angry letter to the Concours, explaining that he was the owner of the Torpedo, not Ida or Tucker, and that they were not allowed to display it. Kerekes didn’t stop there, but continued to state that litigation was pending and to describe a host of complaints he had about Ida and the way Ida had been treating him. Worried about getting involved in the litigation, the concours withdrew its invitation.

The lawsuit

Ida filed suit against Kerekes in New Jersey state court. The complaint presents three causes of action:

- A declaration that there is no contract, or that any contract is unenforceable. That would leave Ida the owner of the Torpedo, with the obligation to refund all moneys paid by Kerekes.

- Improper interference with Ida’s relationship with the Pebble Beach Concours. Ida is seeking compensatory and punitive damages.

- Libel and slander. Ida is seeking an injunction to prevent further defamation and punitive damages.

Whose car is it?

Ida claims that he and Kerekes entered into an agreement to build the Torpedo for $800,000, but no time frame for completion was specified. Ida also claims that, even though Kerekes has made partial payments, there was no agreement as to who would own the work in process.

As a result, Ida claims that Kerekes would not become the owner of the Torpedo until it was completed. Ida claims that he owns the car until it is completed.

Further, Ida claims that because of missing contract elements and the disagreements, there is no enforceable contract between him and Kerekes. So Ida can simply refund the money paid and retain sole ownership of the Torpedo.

All that “Legal Files” can say about this is, “Are they serious?” It is mind-boggling that they can actually claim to be the owner of work they have already been paid for. If that is the law, then all of us need to be extremely diligent about getting very carefully written contracts with all our repair shops.

The lawyers reading this should have already spotted another glaring inadequacy in Ida’s position. If what Ida claims is true, that he owns the Torpedo until it is completed and there is no enforceable contract, then why hasn’t Ida already refunded Kerekes’ money?

Instead, Ida and his legal team ask the court to “authorize” them to do that.

It is fundamental law that if a party is seeking to rescind a contract, the party must “tender” a full refund to the other party. That means they have to try to give the money back, with the other party refusing to accept it, before they can file a lawsuit.

Interference

On the surface, it looks like Kerekes interfered with the Ida-Pebble contractual relationship. Once Kerekes contacted the Pebble Beach Concours, the invitation to show the Torpedo was withdrawn. Whether the technical legal requirements of that claim will be met is not very clear.

To have a claim, Ida must show that it had a contractual agreement with a third party (looks like they did), that the defendant interfered with that relationship (looks like he did), and that Ida suffered damage as a result (they allege damage to their reputation and business).

But Ida must also show that Kerekes interfered by either using improper means or by having an improper purpose.

The means of interference chosen by Kerekes was an email. That hardly seems like an improper means.

If, for example, Kerekes owned a company that was a significant sponsor of the concours, and he threatened to withdraw his sponsorship if the concours allowed the Torpedo to be displayed, that form of economic leverage could be an improper means.

But an email directed to the organizers, not so much.

The email referenced the litigation with Ida, but didn’t threaten to involve the concours. The email also made a variety of arguably defamatory statements about Ida. Those statements could be seen as improper means, but it doesn’t appear that the concours withdrew the invitation because of them.

Ida’s complaint states only that the concours did not want to get involved in the litigation.

Kerekes may also have a pretty good defense to this claim — if he is the owner of the Torpedo, then Ida never had any right to take it to the concours. Kerekes could simply have said, “No, you can’t take my car there.” Thus, the two claims may be intertwined.

Defamation

Ida claims that Kerekes has made a number of disparaging statements about Ida and his business, both orally (slander) and in writing (libel), that are damaging to its reputation. Kerekes should take this claim seriously.

While slander and libel are both defamation, they have traditionally been quite different with regard to proof of damages.

Slander requires Ida to prove actual damages, such as loss of an actual customer or sale resulting from the statement. That can be difficult to prove. However, written statements are seen as more permanent and can be seen by many people, so actual damages do not have to be proven. Instead, damages can be presumed, and punitive damages can be awarded. Thus, letters, emails, Internet posts and the like become more problematic.

Kerekes can defend the claims by proving that everything he said or wrote was true. But that is a very sticky wicket to play. It isn’t enough that the author believesa statement to be true — it must actually be true. “Mostly true” or “pretty close to true” aren’t enough, either. The law requires actual truth. Nor does “he made me do it” work — the law does not see any actual or perceived wrongful conduct as creating any justification for defamatory statements.

In this day and age of the Internet, email and social media posts, we all need to be careful about what we say, as such statements can live forever and cause continuing defamations.

There is nothing private about this stuff. Some people seem to express every thought they ever have on social media, and have no compunctions about telling the world how someone else wronged them.

No matter how badly you may have been wronged, this is not a good idea. ♦

JOHN DRANEAS is an attorney in Oregon. His comments are general in nature and are not intended to substitute for consultation with an attorney. He can be reached through www.draneaslaw.com.

Preston Tucker sure had big dreams. After World War II ended, he embarked on an ambitious plan to design, build and market his own car. His dreams came to fruition, and his eponymous company eventually produced 51 Tucker 48s before it went down in a financial firestorm.

Tucker’s car was identified as the Tucker Torpedo during its design and promotion phase. When the concept was finalized and ready to go into production, Tucker reportedly grew concerned about “Torpedo” reminding people of World War II. So the model was renamed the “48,” for its year of manufacture. Thus, all Tuckers built were 48s, and no Torpedoes were actually built. However, the Torpedo name caught on, and the 48 is frequently incorrectly referred to as a Torpedo.

Preston Tucker sure had big dreams. After World War II ended, he embarked on an ambitious plan to design, build and market his own car. His dreams came to fruition, and his eponymous company eventually produced 51 Tucker 48s before it went down in a financial firestorm.

Tucker’s car was identified as the Tucker Torpedo during its design and promotion phase. When the concept was finalized and ready to go into production, Tucker reportedly grew concerned about “Torpedo” reminding people of World War II. So the model was renamed the “48,” for its year of manufacture. Thus, all Tuckers built were 48s, and no Torpedoes were actually built. However, the Torpedo name caught on, and the 48 is frequently incorrectly referred to as a Torpedo.