SCM Analysis

Detailing

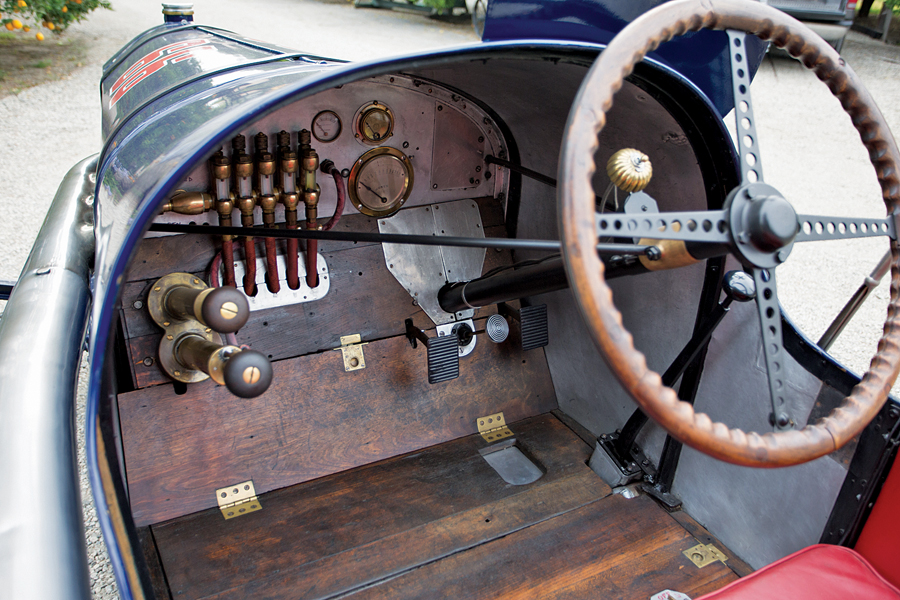

| Vehicle: | 1914 Peugeot L45 Grand Prix Two Seater |

| Years Produced: | 1914 |

| Number Produced: | 4 |

| Original List Price: | £4,000 (about $250,000 today) |

| SCM Valuation: | $7,260,000 (this car) |

| Alternatives: | 1910 Benz “Prinz-Heinrich,” 1914 Delage GP, 1913 Fiat 14-liter GP |

| Investment Grade: | A |

This car, Lot 408, sold for $7,260,000, including buyer’s premium, at Bonhams’ Bothwell Collection sale in Woodland Hills, CA, on November 11, 2017.

It can be argued that our subject car, the 1914 Peugeot L45 Grand Prix/Indianapolis racer, is the most important surviving vehicle in the history of the automobile. Strong stuff? Yeah, but let’s consider the reasons before moving on.

Historical importance is different than beauty, collector lust or even a successful racing provenance — although it can be closely, even intimately, related to these characteristics.

Historical importance has to do with being an essential step that precedes and affects everything that comes after. Being the defining invention that allows development to continue is a prime driver of historical importance.

Surviving paradigm for modern engines

Simply stated, this L45 Peugeot represents the invention of the modern internal combustion engine. It is the essential paradigm that every engine to this day incorporates in its basic design. They only built a few (in varying displacements) before the Great War (World War I) put a stop to racing. Those that were built were very successful in European and U.S. racing, and only two examples remain.

There is a reason this car is valuable — it’s as much prime historical artifact as racing car.

The epicenter of all things automotive

Although Nikolaus Otto and Gottlieb Daimler more or less invented the automobile in Germany, France became the epicenter of all things automotive from about 1890 until the beginning of the Great War.

France had the most manufacturers, the best engineers, the best technology, the best roads, and the most competition, both for market sales and in racing, as manufacturers strove to prove that their machines were faster and more reliable then the others. The first formal race was held in France in 1894, and motor racing became an essential part of the French way of life.

Enter Peugeot

The Peugeot Company was in the automobile business from the very beginning. Starting as a coffee mill and hand-tool manufacturer, they started building bicycles in 1885 and experimented with steam-powered tricycles.

When the machine-tool company Panhard et Levassor acquired the rights to build Daimler’s new automobile engine in 1891, it wanted to market a complete vehicle, so it approached Peugeot about building everything but the engine for them. A deal was reached wherein Peugeot would build vehicles for Panhard — and would also build and sell vehicles under their own brand, using the Panhard engine.

Both Panhard and Peugeot did very well with the arrangement, and in 1897 Peugeot started designing and building their own engines, thus becoming a fully integrated manufacturer.

An internal schism in 1896 had split Peugeot between the automotive side, run by brother Armand, and the bicycle/motorcycle side run by brother Robert. Robert appears to have been the more dynamic, and by 1905 that branch was also building and racing cars under the brand Lion. The Lion brand tended to prefer small, light “voiturette” cars rather than the larger approach. The wounds healed, and the company recombined as a single entity under Robert’s control in 1910.

A giant change

The first decade of the new century was the era of the huge-displacement, low-rpm racing engine, with 10-, 14- and even 16-liter monsters trying to get horsepower advantage by simply getting bigger — not by improving on the basic efficiency. By about 1910, the time was ripe for serious innovation.

French society at the time was highly stratified, with the educated engineers working on their designs insulated from — and contemptuous of — the working-class drivers and mechanics who had to make them work. However, Robert Peugeot was now running the show, and he was determined not to allow possible innovations, whatever their source, to get past him, so when he was approached by three of Lion’s driver/mechanics with completely radical ideas about how to design an engine, he was willing to listen.

He made a deal with them to set up an entirely separate shop to design and build a series of Grand Prix cars for £4,000 each, which infuriated the regular Peugeot staff. They immediately branded the three “Les Charlatans” — posers who were destined to fail miserably.

The “Charlatan” driver/mechanics in turn hired a Swiss draftsman, and the four set to putting their ideas into reality in a new 4-cylinder engine.

This sort of arrangement was not unknown for Robert Peugeot, as he made a similar deal with a young designer named Bugatti, but that is a different story.

The first double-overhead-cam engines

The idea of overhead valves in a combustion chamber was well established by now, but the operation had been by complicated pushrods and rockers.

The Charlatans’ idea was to put the cams up above the valves —the first double-overhead-cam design. They also went to four valves per cylinder with a pent-roof piston (does this sound familiar?). Porting could now be straight through and very efficient.

Displacement of the first design was 7.6 liters, and the cars debuted at the 1912 Coupe de l’Auto, a 956-mile marathon held over two days. Peugeot won over 14-liter Fiats, and Peugeot had set the new standard.

Displacement was reduced to 5.6 liters for 1913 (L56) in response to new racing regulations, and the bottom half of the engine was completely redesigned. The new crankcase was a barrel shape cast from aluminum — light and amazingly strong — with three ball-bearing mains and the first known use of a dry-sump oiling system. The cams were now driven by a gear tower in front, also a first, as was making the intake valves larger than the exhausts. This new engine could be revved to an amazing 3,000 rpm safely, and it became the definitive form of the Charlatans’ Peugeot engine. The 1914 version of the GP car dropped the size to 4.5 liters (L45) and added four-wheel brakes.

Running at Indy a century ago

European Grand Prix was home, but Indianapolis was easily the world’s richest race, and money beckoned, so Peugeot entered two L76-based cars for 1913. One broke, but Jules Goux, one of the original Charlatans, won, and the world took notice.

In 1914 Peugeot took 2nd and 4th at Indianapolis in a pair of Delage racers, but World War I broke out, and racing in Europe stopped. Peugeot was swamped with war issues and abandoned anything to do with racing.

An American who was racing an L56 broke the engine badly at a race in California, but with Peugeot unavailable, he took it to Harry Miller’s Los Angeles shop to get it repaired. Miller fixed the engine — and also appropriated the design. This was the beginning of a 50-year run of Miller, Offenhauser and Meyer-Drake racing engines.

Bugatti’s twin-cam engine was copied from Miller. The Charlatans’ design became immortal.

Our subject Peugeot L45

The war paralyzed Europe, but Indianapolis still had a show to put on, so in 1916 promoter Carl Fisher searched Europe for competitive cars to bring over. He found two L45s — one of them is our subject car, the 1914 Lyon Grand Prix spare — and brought them to Indianapolis. Driver Ralph Mulford brought it home in 3rd place. Racing ceased when the U.S. entered the war, but it reopened in 1919, and various Peugeots continued to run at Indy and around the U.S., including our subject car.

Although there were probably six to eight Charlatan cars in the beginning, they gradually disappeared, leaving this L45 and an L30 as the sole surviving examples of a monumentally important automobile design.

An artifact, a paradigm and a survivor

So this car is where it all began. Virtually every automobile engine built in the past hundred years owes a debt to the genius and inventiveness of the Charlatans and their wonderful Peugeot racers.

This is the paradigm that changed the world of automotive design, and as such, is arguably the most important automotive artifact that exists. Only the person who chose to buy this amazing car at auction could set its value, thus I will say it was fairly bought. ♦

(Introductory description courtesy of Bonhams.)