SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Vehicle: | 1954 Maserati A6GCS/53 Spyder |

| Years Produced: | 1953–55 |

| Number Produced: | 52 |

| Original List Price: | N/A |

| SCM Valuation: | $1,685,000 |

| Chassis Number Location: | Tag welded on front cross member |

| Engine Number Location: | Stamped on head |

| Club Info: | Maserati Owners Club |

| Website: | http://www.maseratiowners.club |

| Alternatives: | 1954–55 Ferrari 500 Mondial, 1953–55 Aston Martin DB3S, 1951–53 Jaguar C-type |

| Investment Grade: | A |

This car, Lot 103, sold for $3,001,485, including buyer’s premium, at Artcurial’s Rétromobile Auction in Paris, France, on February 9, 2018.

Readers familiar with evolutionary biology may be familiar with a theory referred to as “punctuated equilibrium,” championed by Stephen Jay Gould. The very short-form explanation of this theory is that rather than proceeding in a long, more or less constant process, biological evolution happens in a number of sudden, discrete jumps followed by periods of relative constancy.

The veracity of this concept is not the subject of my profile, but I will argue that racing automobiles have evolved in a series of sudden bursts of creativity followed by periods when the new ideas are normalized — followed in turn by another burst.

As an example, look at the post-war development of racing cars. The 1940s were a difficult time economically and politically, and the cars of the time were basically variations of pre-war racers in both concept and mechanical components.

The first post-war generation of racers arrived in the early 1950s, led by Jaguar’s C-type and Mercedes’ W194 (300SL racing prototype). These racers introduced aircraft-engineering practices to design, construction and aerodynamics in a huge change from the previous practices.

The Italians were not exactly leading this parade, but they responded in 1953 and 1954, particularly in the under-2-liter category. This is the context in which we should consider the Maserati A6GCS/53 — it is the first generation of post-war Maserati racers.

At the start

Let’s open with bit of history. In the beginning, there were four Maserati brothers who trained as automotive engineers and loved racing.

Beginning in the mid-1920s, they started building racing cars under their own name and had immediate success, not least because Alfieri, the charismatic lead brother, was an excellent designer and a brilliant driver.

Much like modern day Lola or March, Maserati had zero interest in building road cars. Their business was building racing cars to sell to customers. Another interesting detail is that their cars were always supercharged — it was part of the brand.

Unfortunately, Alfieri was badly hurt in a racing accident in 1927. Although he returned to the company, his recovery was incomplete. He had surgery to repair some of the damage in 1932, and he died on the operating table, which left the remaining brothers in a difficult position.

Brother Ernesto took up the lead and was a brilliant designer, but the mid-1930s were a terrible time for any business, much less a racing-car specialist. So in 1937, the brothers sold the company to the Orsi Group, a very wealthy industrial conglomerate that promised to provide financial and management stability while continuing the company’s traditions.

The brothers all signed a 10-year employment contracts and continued to build supercharged racing cars until World War II intervened, and the company turned to making machine tools.

Enter the A6G

The A6G terminology is interesting. Ernesto spent much of World War II dreaming of — and designing — a non-supercharged 1,500-cc GT car for a peaceful future. He named the project A for his brother Alfieri and 6 for the number of cylinders.

In 1944, he revised his dream to make it a 2-liter single cam and decided to make it with an iron block to save expense, thus the A6 added G, which stood for “Ghisa,” or iron block. After the war, Maserati actually started building the A6G cars, so the nomenclature stuck even after Ernesto and his brothers departed to form OSCA in 1947.

Maserati had yet to build a road car, so all of the cars they built were now A6GC (C for Corsa, competition) and either S (Sport) or M (Monoposto).

The engines had long since stopped being an iron block in favor of aluminum, even though the G remained in the name. Gioacchino Colombo became chief engineer for Maserati during a classic Italian talent shuffle in 1952.

Colombo came from Ferrari, where he had just created the iconic V12 engine before Lampredi replaced him.

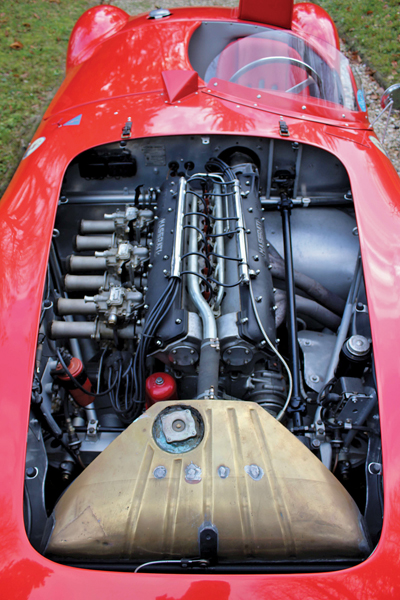

At Maserati, Columbo proceeded to completely revise the existing A6G design with an eye towards making it competitive in the new generation of competition cars. He changed the engine bore/stroke ratio to make it highly oversquare (big bore, short stroke), with the larger bore allowing for larger valves and a second spark plug per cylinder. The shorter stroke allowed for higher RPM.

Colombo abandoned the earlier Sport chassis design in favor of widening the 1952 Monoposto chassis to a 2-seater. He also dropped the earlier cycle-fender body design for a new and more aerodynamic envelope approach.

The new car was alternately called the “Maserati Sports 2000” or the more traditional “A6GCS/53.” The car proved a resounding success in its category. Relatively small, with a new-generation chassis and 170 horsepower pushing 1,600 pounds, it had excellent handling and better power to weight than a C-type, but with a 2-liter engine it didn’t have the legs for races like Le Mans. It was really never intended for this purpose.

Still a race car builder — not runner

It is worth remembering that Maserati at the time was strictly in the business of building and selling racing cars — not of trying to win championships.

The FIA World Sports Car Championship was established in 1953, and Jaguar, Aston Martin, Ferrari and Lancia were going hammer-and-tongs to win, but they all had road-car sales to support the effort. Winning required at least 3 liters of horsepower.

With the exception of a few selected races such as the Mille Miglia and Targa Florio that suited their smaller car, Maserati wisely avoided factory racing and concentrated on selling great cars to privateers. They had a devoted clientele, and many at the time —and even now — consider Maserati to be mechanically superior to Ferrari.

Ferrari followed the market niche, and in 1954 introduced the 500 Mondial, which was a 2-liter, 4-cylinder with very similar specifications to the Maserati. The 500 Mondial was Ferrari’s first-ever bespoke racing car actively sold to customers.

OSCA marketed their MT4 racer with engines ranging from 1,100 cc to 1,600 cc. Between the three builders, something like 100 racing cars were sold — mostly in Italy. Maserati originally sold 36 of the 52 A6GCS/53 built to Italian buyers. A similar percentage of Italians bought Ferrari. Eventually, a large number of all of these cars migrated to the burgeoning American racing scene, but they were originally intended for the home market.

On to road cars

The broader significance of the A6GCS/53 is that it provided the economic success that allowed Maserati to make the transition from a specialty racing car manufacturer to a primarily road-car company.

Although most of the A6GCS/53 cars were Corsa Spiders, four were built as berlinettas, including two Pininfarina coupes that qualify as the most heartbreakingly beautiful cars of the entire decade — and showed the way to a production future.

In 1954, Maserati introduced the A6G/54, a de-tuned, purely road version of the Corsa and the beginning of the new Maserati. From that point forward, although they continued to build racing cars, Maserati would be in the road-car business as a primary focus.

The company had grown up.

The best of the best

When you look at the various determinants of racing-car collector value, it’s hard to get much better than our subject car. It’s Italian, mechanically exotic, rare, aluminum-bodied, historically significant, relatively user-friendly — and beautiful.

On the downside, it is a 1953-design, 2-liter racer, so it is less powerful and not as quick or comfortable as the second-generation cars that followed.

If there is such a thing as an entry-level Italian racing collectible, this is probably it. The sale price of $3 million may seem like a lot of money, but I’m not sure where you are going to find anything even close for less, so I will say fairly bought. ♦

(Introductory description courtesy of Artcurial.)