SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Vehicle: | 1956 Elva Mk 1/B Sports Racer |

| Years Produced: | Mk 1, 1955; Mk 1/B, 1956–57 |

| Number Produced: | Mk 1, 6; Mk 1/B, roughly 14–25 |

| Original List Price: | $3,000 to $3,500 |

| SCM Valuation: | $60,000 |

| Chassis Number Location: | Tag on frame tube in engine compartment |

| Engine Number Location: | Right front of block |

| Club Info: | Elva Owners Club |

| Website: | http://www.elva.com/elva-owners-club.html |

| Alternatives: | 1956–58 Lotus Eleven, 1955 Lotus Mk IX, 1956 Cooper T 39 “Bobtail” |

| Investment Grade: | B |

This car, Lot 36, sold for $165,399, including buyer’s premium, at Bonhams’ Zoute Sale in Knokke-Heist, BEL, on October 5, 2018.

Although I write monthly about an incredible range of racing cars, fundamentally I am an Elva guy.

I have been racing Elva sports racers (Mk 6 and Mk 7) for over 30 years, I oversaw the acquisition of a collection (now mostly dispersed) of every significant Elva ever built, and I have personal experience with virtually all of them.

The true ultimate anorak and guardian of the brand is Roger Dunbar in the U.K., but I do know my way around Elvas. So I feel qualified to make this sweeping generalization: In its relatively short history, Elva grew in expertise and sophistication to a point where it easily matched Lotus and Brabham in sports racer design, and evolved into the company that produced the customer McLaren Can Am racers, but it did so from extremely humble beginnings.

The Elva Mk 1, as represented in today’s subject car, was the ultimate in humble beginnings.

From the beginning

Frank Nichols came out of World War II as a young man with mechanical ambitions, and he soon established the London Road Garage — a successful auto repair and used-car dealership.

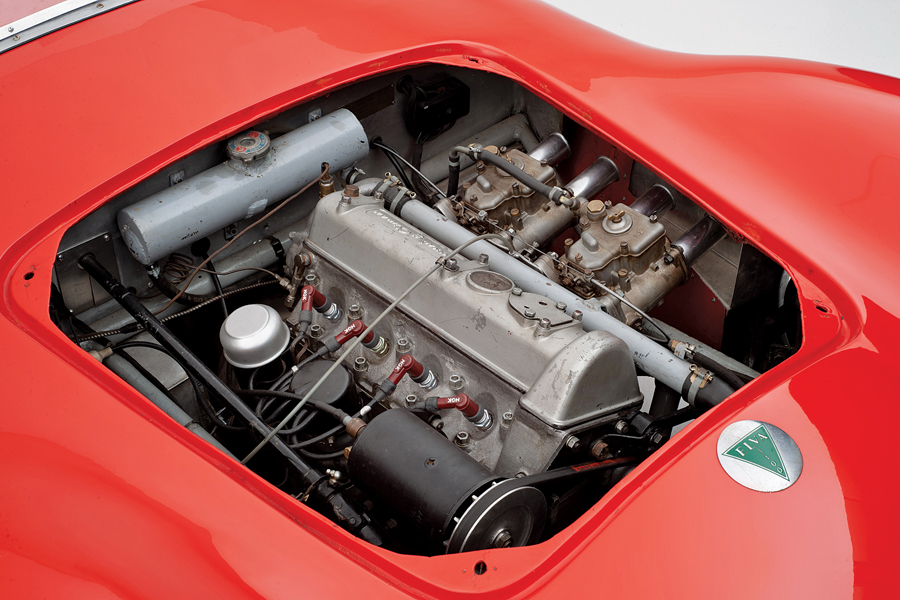

Automotive enthusiasm was growing in the early post-war years, but austerity in Great Britain meant that virtually nobody had any money. Ford of England in those days sold the Prefect, a small sedan with an iron 1,172-cc flathead four for power, and it became the basis for lots of “everyman” racing. In 1953, Ford upgraded the car to the “100E” with an improved version of the same engine that made a whopping 36 bhp.

Frank had attracted a small team of innovative mechanical engineers, and “Mac” Witts came up with an “inlet over exhaust” conversion for the 100E that left the exhaust in the block but moved the intake into the cylinder head, allowing far better breathing and substantially improving the available horsepower.

Frank quickly began producing and selling this IOE conversion to enthusiastic customers.

As opposed to Colin Chapman of Lotus and most of the other young racing car entrepreneurs, Frank Nichols was not a racer himself. He was primarily a businessman who saw an opportunity on the performance side.

Nichols decided that an excellent way to promote this conversion would be to build a racing car to demonstrate the engine. So he had a friend build a one-off called the CSM. When the car did well, Frank decided to get into the car construction business with a short run of an improved version of the CSM.

London Road Garage (LRG) wasn’t a very inspiring name, so Frank adapted a comment made by a friend watching the CSM perform: “Elle va!” or “she goes” in French. Elva thus took its place in the ranks of racing-car manufacturers.

Crude, cheap — and fast

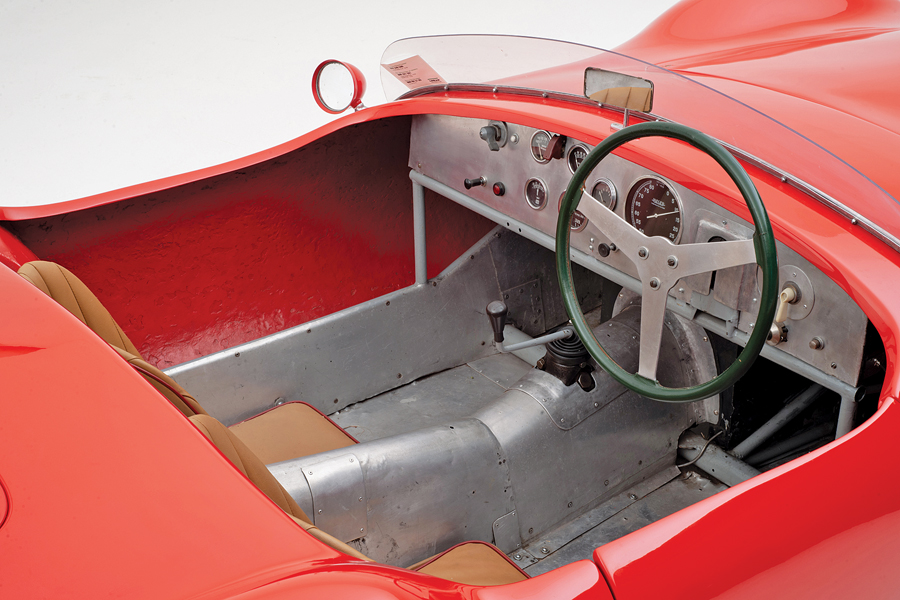

The first cars were built in the London Road Garage, beside the regular used-car business, and were decidedly crude. The frame was a simple ladder arrangement using medium-diameter round tubing with a smaller-diameter triangulated structure above it for strength and rigidity. The drivetrain was adapted from the Ford Prefect, and the entire front suspension with springs, shocks and steering was lifted intact from a Standard Ten sedan and welded to the front of the frame assembly.

We had a Mk 1 (#06), and the build quality, particularly the welding, would have disappointed your high-school shop teacher.

Aluminum bodywork was standard for racers of this era, but Nichols understood that price and delivery time were a huge concern in selling cars. So after using a few alloy bodies, Elva hired Ashley Laminates (later Falcon) to build a fiberglass shell using the alloy body as a mold.

The complete body was then fitted over and bolted onto the running chassis. It was only a few bolts, so for any serious work, the easiest solution was to unbolt and lift the entire body off the chassis. It didn’t take 20 minutes. These cars were simple, crude and cheap, but also effective. And the cars sold.

Enter the Mk 1/B

The initial expectations were not particularly high, so after supplying a small number of cars, Elva realized that they were maybe on to something. They proceeded to upgrade the whole situation, which is where the Mk 1/B arrives.

Production was expanded into a second workshop — the back of a neighboring fish-and-chips storefront — and the front suspension was revisited.

Nichols had a proper fabricated front suspension with tubular A-arms and coil-over shock/springs designed, incorporating a steering box with better geometry. The Climax FW racing engine and a BMC 4-speed transmission was offered as an alternate to the original Ford with 3-speed of the earlier cars. Construction quality improved markedly. This was the first step in Elva’s journey toward becoming a serious constructor.

The next important event was when American racer Chuck Dietrich discovered the Mk 1. He bought one and set himself up to be the U.S. distributor, opening up a lucrative market.

Dietrich was a very competitive racer in his own right, and he appreciated what he saw as Elva’s essential characteristics: It was good enough and it was cheap. Chuck freely acknowledged that Lotus and Cooper made better cars, but at about $3,000 in the U.S., the Mk 1 was about half the cost of a Lotus, and a good driver could go play with them and occasionally win. All of the Mk 1/Bs destined for the U.S. carried Climax power.

Is it an Mk 1 or Mk 1/B?

Our subject car poses several irksome inconsistencies. The stated history has it originally delivered to the U.S., and the chassis number makes it one of the last Mk 1/Bs — built while Elva was starting on the far more sophisticated Mk II.

At my request, Roger dug into his files and sent me a photograph of our subject car’s chassis with its body off. The front suspension is clearly production Standard sedan — not the later fabricated Mk 1/B design. Roger is sure that his photo is of the correct car, and the Climax engine and other details seem correct, so what is it, Mk 1 or Mk 1/B?

Far more bothersome is the price paid for the car.

While later Elvas soared in sophistication, competitiveness and collectibility, the Mk 1s were really more of a home-built chassis with a commercial body bolted on. They were not particularly good, had no real competitive success, and nobody I know considers them to be collectible.

Why someone would pay the sale price for our subject car is beyond any of us. Roger recently sold one of the best Mk 1/Bs around for about half the subject car’s price — and was pleased.

A few years back, I sold our Mk 1 (admittedly, with engine problems) for $25k and was happy to do so. Something doesn’t add up here.

For lack of any good logical justification, I am stuck with conjecture. The car had been offered before the auction with an ask of $170k, so it seems someone thinks it should be worth the money.

Clearly, though, this buyer wasn’t conversant with the current market. It is possible that the buyer was one of those automotive investment funds and saw it as equivalent to and cheap compared with the $225k and up required for a Lotus Eleven or Cooper.

If that is so, the Elva community should hope they are correct and Elva values are skyrocketing. Otherwise, it was extremely well sold. ♦

(Introductory description courtesy of Bonhams.)