SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Vehicle: | 1956 Lotus Eleven Le Mans Series I |

| Years Produced: | 1956–57 |

| Number Produced: | 98 (Le Mans version) |

| Original List Price: | $5,467 |

| SCM Valuation: | $209,000 |

| Chassis Number Location: | Tag on radiator ducting, right side by plug |

| Engine Number Location: | Boss on right front of block |

| Club Info: | Lotus Eleven Register |

| Website: | http://www.lotuseleven.org |

| Alternatives: | 1956–57 Elva Mk II, 1955–56 Cooper T 39 “Bobtail,” 1953–56 Porsche 550 Spyder |

| Investment Grade: | A |

This car, Lot 133, sold for $92,960, including buyer’s premium, at Bonhams’ Amelia Island Auction on March 8, 2019.

By the mid-1950s, Jaguar and Aston Martin were the premier British participants in the international racing-car scene, but they had the advantage of being pre-existing large export manufacturers with a focus on large-displacement racers for the championship wars.

Lotus at the time was a motley band of enthusiastic kids in little more than a garage cranking out a few hand-built small-displacement racers for the local club-racing market. They built about 25 total cars in 1955.

The Eleven arrives

The new model Eleven was going to be Lotus’ step into serious volume production, and the beginning of its growing up as a company.

The car proved to be exactly that.

Available as the racing IRS “Le Mans” or as live-axle “Club” and “Sport” street versions, Lotus ended up building 150 total Elevens in 1956 and 1957. Shockingly low, fast, and beautiful for its time, the Eleven established Lotus as a manufacturer to be reckoned with internationally — and it remains the most successful racing car Lotus ever built.

The iconic shape, driving excellence, and racing dominance have combined to make the Eleven highly collectible in today’s world, but, as always, it can be a bit more complicated than that.

Why sold so cheaply?

The best, most-collectible Lotus Eleven Le Mans in the world is worth probably $475,000 today, and a good, known-history racing Eleven is comfortably over $230,000. Today’s subject car, which is arguably the same thing, sold for about one-fifth that amount. What gives? Did somebody just get the deal of the year, or did the price reflect the true value?

The answer is most likely the latter, and figuring out why is our topic today.

Let’s start by considering the essence of collectibility in vintage racing cars. Historical significance, particularly being an important inflection point in the development of the modern racing car, and racing success as well as physical beauty are core components.

Probably the most important physical characteristic in collectibility is having aluminum bodywork. Fiberglass-bodied cars just don’t carry the desirability of aluminum bodywork. An excellent example is the Lotus 17, the successor to the Eleven in its class and a far better racing car using the same mechanical package but with a fiberglass body. It is worth maybe half of an equivalent Lotus Eleven.

The non-physical components such as history, originality, authenticity and provenance, are easily as important — and often far more so — but how do you prove that a car is real? The only correct answer is in provenance — ownership, usage and maintenance records that go back, ideally, to the beginning.

Unknown provenance hurts value

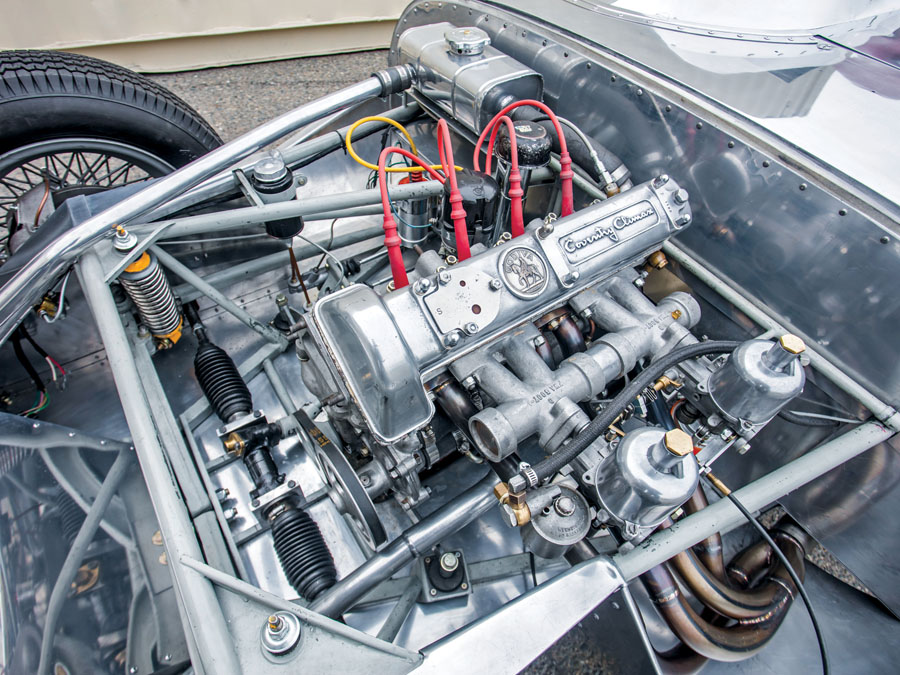

Chassis numbers are extremely important, but Lotus didn’t stamp the frames. The only evidence was a little tag pop-riveted onto the aluminum sheet beside the radiator, and they disappeared early and often.

Engine numbers don’t really count for Lotus, either. As opposed to Ferrari and Maserati, who built and numbered the components with each chassis, the Climax engines for these cars were more like cartridges in a rifle. They were used and replaced virtually every race. “Matching numbers” is a useless concept here.

From a collector standpoint, this car doesn’t offer much. The chassis number and provenance are completely unknown, and it was built from an old, wrecked frame relatively recently. At best, only a few original parts were used.

This car may be the reconstruction of a famed racer, but it is more likely just an old wreck. There is really no way to know one way or another.

Lots of racing value

The Lotus Eleven was one of the great racing cars of the 1950s and remains a joy to drive — and particularly to race. The racing grid for late-1950s sports racing cars is prestigious, fun and highly competitive, so let’s talk about this car as a pure racer. To do so, I will need to detour briefly into details about Climax racing engines.

The Coventry Climax FW (Feather Weight) engine was originally designed as a portable fire-pump engine for the British military, but its architects were serious performance guys, so it used a single overhead cam and was very light and powerful.

It quickly morphed into a racing engine. The original version was called FWA and was effectively limited to 1,100 cc by the block, but it was perfect for British club racing. Most racing Elevens used this engine. Originally, Climax used two SU carburetors, but the serious racers all switched to double side-draft Webers for more power.

For 1.5-liter classes, Climax developed the FWB engine block, which was basically identical but had room for a larger bore and relief bumps in the side to clear a longer stroke crank. This allowed 1,460-cc displacement.

For serious racing, they also revised the cylinder head to use a five-bearing camshaft (vs. three in the normal version) that allowed for a more aggressive cam and higher rpm. All of these pieces are completely interchangeable, so the mix-and-match options for Climax FW blocks and cranks are 1,100-, 1,220- and 1,460-cc with either a mild or serious racing cylinder head. The horsepower range for the variants is from about 75 to 125 hp, and all are legal for racing Lotus Elevens.

Wanna race? The car needs a new engine

From a racing standpoint, the problem with our subject car is that it carries an FWA engine with SU carburetors that claims 83 hp and it isn’t prepared for racing. The engine means that you are going to run about 40 hp shy — which is about two-thirds of the competition’s power.

The FWA block can’t be stretched, so being competitive is going to cost about $25,000 for a strong FWB with Webers. Add to that the costs of setting it up as a proper racer and you are looking at a minimum of $35,000 to put it on the track.

A flawed beauty

So, we are looking at a beautiful and correct car that can make a claim to be a 1956 Lotus Eleven, but it has no chassis number or provenance. At most only a few original pieces are still in the car, so it has little — if any — collector value.

As a racer it will be welcome at most any event (though possibly not the snooty ones), but it will cost a serious chunk of cash before it can be fielded as a safe and competitive entry. Sitting in someone’s collection, it will look as impressive as one costing four times as much, but it will never be an important Lotus.

As such, the car is beautiful and pristine, but seriously flawed no matter what someone’s motivation for buying it may be, and today’s market is notoriously unforgiving of compromised product.

The seller was probably disappointed, but it is what it is. I would say a rational buyer got the car at a fair-to-well-bought price. ♦

(Introductory description courtesy of Bonhams.)