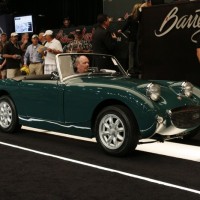

Restored Bugeye finished in British Racing Green with new black interior and new black top. Mechanical upgrades include a fresh rebuilt 1,275-cc motor, disc brakes, aluminum flywheel, aluminum radiator, dual SU carburetors, free-flow exhaust, alternator, high torque starter and spin-on oil filter.

SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Vehicle: | 1960 Austin-Healey Bugeye Sprite |

| Number Produced: | 48,987 |

| Original List Price: | $1,795 |

| Tune Up Cost: | $350 |

| Chassis Number Location: | Stamped on a metal plate secured to the left-hand inner wheelarch valance, under the bonnet. |

| Engine Number Location: | Stamped on a metal plate secured to the right-hand side of the cylinder block, above the dynamo. |

| Club Info: | Austin-Healey Club of America, Austin-Healey Club USA |

| Website: | http://www.healeyclub.org |

This car, Lot 341, sold for $20,350, including buyer’s premium, at Barrett-Jackson’s 2013 Palm Beach sale on April 12, 2013.

Everyone knows the story of the Austin-Healey Sprite, and some of it is actually true. A few years after the Austin-Healey 100 came to market in 1953, Donald Healey tasked his company to create an entry-level sports car that was to be so small that “a chap could put it in his bike shed.” The design brief was simple: “A small and inexpensive sports car.”

Gerry Coker, the man who had designed the Austin-Healey 100 to rave reviews at the 1952 London Motor Show, was given the assignment.

Thus in 1957, Coker drew a car that borrowed design elements from Ferrari — really — and that would be easy and inexpensive to make. The little car had exterior door hinges, a grille that tilted noticeably forward at the top (à la Ferrari), a large rear-hinged bonnet that consisted of nearly the entire front half of the car and gave great access to the engine bay, and bonnet-mounted headlamps that reclined backwards, looking up at the sky, when not in use. The overall effect was original and stylish. And it was small.

Big, goofy headlights

Later that year, Coker left the Donald Healey Motor Company for greener pastures and greater opportunities in Detroit. Then, virtually as soon as he turned his back, “corporate design” reared its often-unattractive head and nixed the headlights to save money. Several other smaller changes were made to make the car even less expensive to produce.

Most notably, the reclining headlamps were fixed and mounted in pods shaped like big cartoon bullets, but they were not relocated to the wings where one might reasonably expect to find fixed headlamps. Instead, they were smack on the bonnet, close together, disproportionately large — and formed the new, unintentionally dominating design element of the car. What had begun as a stylish car with a little Ferrari influence had become — in an instant — a cartoonish rendition of a small sports car.

Fast forward to the summer of 1958. Sprite production had begun in March with the official debut two months later, and by summer, dealers in the United States received the first cars. One of Coker’s colleagues in Detroit invited him to come along and have a look at his creation.

When they arrived at a dealer’s showroom and spotted those bulbous headlamp pods, Coker’s only comment about the design was, “Not mine!” Yes, those headlamps were inelegant. Yes, they were incongruous. Yes, they were, well, just silly looking. But as happens occasionally in car design history, what begins as a gross error becomes an endearing trademark flaw — perhaps in the same way that a mole becomes a “beauty mark” on an actress. In this case, the Sprite got two really big beauty marks.

Everything but fast

Austin made just short of 49,000 Bugeye Sprites from March 1958 to November 1960, and the model went on to endear itself to generations of sports-car enthusiasts. The car performed miracles on the track, in rallies, and in many owners’ social lives as well. In short, it was everything that a sports car should be, with the possible exception of fast. With its original 948-cc engine, the Sprite took about 20 seconds to reach 60 mph, so whiplash and speeding tickets were uncommon among owners.

The car presented here is an excellent example of a Bugeye that is ready to be driven, and with all of the right mods. Although described as British Racing Green, the color looks like a very good match to an early Big Healey color named Spruce Green.

Although neither British Racing Green nor Spruce Green was ever offered on the Sprite, the color suits the car well and is (very nearly) period-correct for the marque. The Panasport wheels are a great look on these cars, and they are oh-so-much easier to clean than wire wheels, not to mention much stronger.

The headlamp wire-mesh screens are of course an add-on, but are also easy to remove if the new owner prefers the cleaner, less-cluttered look without them. The exterior rear-view mirrors are thoughtfully mounted on the windscreen frame posts, thereby avoiding the need to drill holes in the bodywork.

Bugeye Fun Fact #17: Front bumpers were optional. That said, almost all of those sent to the United States were optioned out with all the bells and whistles, or in this case, “bumpers and heaters.” Yes, heaters were optional on this affordable, entry-level model. So that means that to the Bugeye cult, this front-bumperless example looks perfectly fine — in fact, many prefer the sportier, less-heavy, less-cluttered look without the largely pointless front bumper. After all, it was mounted too low to function as anything more than a big chrome curb feeler.

Smart mods on a blank canvas

It is the engine bay of this example where the restorer really left the originality guide on the nightstand, painting the cylinder head (from a Mini Cooper S) red and the rocker cover black, and framing it all in flat black on the surrounding body panels. That said, it’s tidy enough, and besides, Bugeyes have long been viewed as blank canvases for improvements and modifications anyway. Hardly anyone restores one to precise original specs and appearance.

However, one deviation from original that some may consider objectionable is the replacement of the simple, black Smiths gauges with some from the Smiths classic “Magnolia” line of gauges with cream-colored faces. These look like something more appropriate for an upscale 1920s or 1930s car. On the Bugeye, they’re an off-theme distraction.

But the major mods on this car read like a list of the top must-do items:

Replacing the original 948-cc engine with the nearly identical-looking 1,275-cc version is “a good thing” — in the sub-100 horsepower category, every pony counts.

Swapping the tiny original front drum brakes for discs will deprive you of frequent opportunities for adrenalin rushes provoked by the marginal original brakes, but save those rushes for something besides a series of near rear-enders.

The aluminum flywheel and aluminum radiator are important, as every pound saved is a pound earned. The alternator is also a good idea because the novelty of the Lucas generator wears off quickly when its rear bearing goes bad and the sound is like that of a blender full of marbles. Take it from someone who knows.

The high-torque starter will deprive you of opportunities for push-starting the car, but if you miss those, find a gentle incline near your home and have your fun push-starting it there and not on an upward incline on the shoulder of a busy freeway during a rainy night.

The spin-on oil filter makes oil changes much less messy. While you may miss the feeling of oil running down your arm when changing oil with the original metal filter canister and felt washer, save the kinky stuff for quiet weekends at home.

This Bugeye has all the smart mods, terrific color, the best-looking wheels, and “front bumper delete” to borrow some Detroit lingo, and the total package equals The One You Want for a Bugeye to actually drive. Call this sale market-correct. ?

(Introductory description courtesy of Barrett-Jackson.)