SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Vehicle: | 1963 Jaguar XKE lightweight competition racer |

| Years Produced: | 1963 |

| Number Produced: | 12 |

| Original List Price: | N/A |

| SCM Valuation: | $1,817,800 (Lightweights seldom come to market, so this has skewed the median price very low) |

| Chassis Number Location: | Right front wheelarch |

| Engine Number Location: | On head between cam covers, and on right side of block above oil lines |

| Club Info: | Jaguar club of North America |

| Website: | http://www.jcna.com |

| Alternatives: | 1959–62 Ferrari 250 SWB, 1959–63 Aston Martin DB4GT, 1962–63 Shelby FIA Cobra |

| Investment Grade: | A |

This car, Lot 24, sold for $7,370,000, including buyer’s premium, at Bonhams’ auction in Scottsdale, AZ, on January 19, 2017.

The mid-1950s were an incredible party for Jaguar from the competition standpoint, with the success of the C-type followed immediately by their D-type, both of which were utterly dominant during their glory years. It all culminated at Le Mans in 1957, with D-types finishing 1-2-3-4-6 in a triumphal procession. The D-types also had good success later in the year.

The spring of 1958, however, dawned gray and hungover, as Jaguar tallied the costs of their success. Running a factory team had been frighteningly expensive, and they were stuck with a raft of brand-new D-types that they couldn’t seem to get rid of. Although the D-type was still a great car, racing was moving on, and, at best, the D-type was a mediocre street ride.

This lesson was not lost on management.

Henceforth Jaguar’s racing efforts would concentrate on cars that would sell well to the general public and be great racers — in that order.

Enter the E-type

Jaguar’s new sports car would clearly be a development of the D-type concept. Serious production development started in early 1960, and the Jaguar E-type was introduced to the world in March 1961.

Steel was used instead of aluminum for the monocoque chassis and body panels, and a new IRS rear suspension with inboard disc brakes was introduced. The engine and drivetrain were standard Jaguar.

It was gorgeous.

On its introduction, Enzo Ferrari reportedly said that it was “the most beautiful car ever made.” Jaguar’s competition department managed to divert seven early-production cars to become racers. These were basically stock roadsters with breathed-on engines, stronger clutches and close-ratio transmissions.

Ready for racing

It was a fortuitous time for introduction of a modern, fast GT car. The FIA, having run its championship for small production sports cars for years, had decided to move the championship to homologated GT cars starting in 1962, so the serious players were all stepping up in anticipation of GT being the main event.

Ferrari had their 250 SWB well sorted and Aston Martin had countered with the DB4GT, so the stage was set for some very serious competition.

Jaguar had abandoned running a factory team, and instead used a few closely associated private teams to field the actual cars, while the competition department stood ready to supply them what they needed in preparation, parts and advice.

One of their favorites was John Coombs, a Jaguar dealer from Guildford. He and Equipe Endeavour got the first two cars, both of which were entered in the Oulton Park event in April. Running against both SWBs and DB4GTs, the E-types finished 1st and 3rd, replicating the XK 120 and C-type tradition of winning the first time out. In May they went to Spa for their international debut, and one finished 2nd sandwiched between two Ferraris. Jaguar had clearly set a marker.

One who certainly noticed was Enzo Ferrari. In response to Jaguar’s new challenge, he set his engineers to creating the legendary 250 GTO with an eye towards the 1962 FIA manufacturer’s championship.

Ferrari’s 1962 challenge

For 1962, Jaguar fielded essentially the same teams with the same cars as 1961, but with ongoing detail improvements made over the winter to make the cars both faster and more dependable.

Ferrari, on the other hand, introduced the GTO. The new GT championship was for homologated production cars with a minimum production of 100 units, which the GTO couldn’t meet, but there was a side door available.

In deference to the day when cars used a chassis and engine/drivetrain with bodywork attached over it, the FIA had a provision that allowed “alternate bodywork” on production cars, so Ferrari presented the GTO as simply a special body on a 250 SWB. Although Ferrari’s claim was blatantly false, the FIA was worried whether the new GT category would provide exciting racing, so they weren’t about to question their strongest entrant. The GTO was accepted as “Omologato.”

The GTO made life very difficult for Jaguar in 1962. The E-types had more torque and were arguably better handling, but they were 150 pounds heavier and didn’t have the top speed of the GTO.

In addition, according to Graham Hill, the E-type racer still felt like a touring car, as it had never been fully developed for racing. Both Coombs and Hill fought with the factory to get chassis changes made, but they seemed to only irritate the competition department, who were confident that they alone knew how to make the cars work (BRM was notorious in this period for not allowing their F1 drivers to even suggest tire-pressure changes, so the arrogance wasn’t unusual).

At one point Jaguar sent Coombs a letter suggesting that he should stick to managing a team — if he could do even that. Wildly frustrated, Coombs did what any serious team owner would do: He went and bought a GTO.

Needless to say, this caught Jaguar’s attention. Their attitude changed immediately.

John Coombs was not unreasonable, so he cooperated fully with Jaguar’s newfound enthusiasm for creating a better E-type racer. Coombs even loaned the factory his GTO so they could study it.

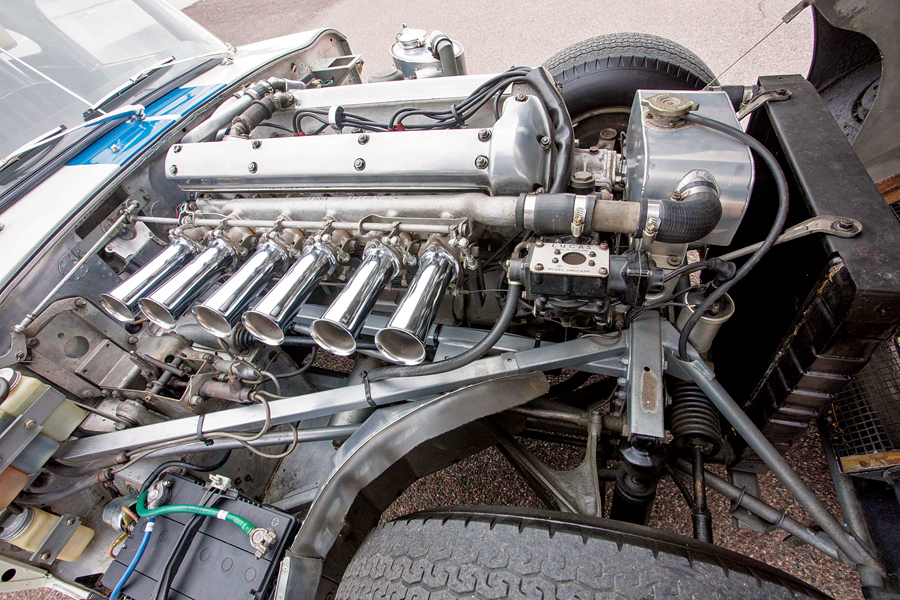

In return, Jaguar offered to take his original 1961 E-type and modify it accordingly. The steel chassis was thrown away and replaced with an aluminum one, the bonnet was changed to aluminum, and a new aluminum-block 3.8 liter engine was installed with a wide-angle cylinder head, dry-sump lubrication and Lucas fuel injection.

The original windscreen was retained (FIA rules), but an alloy hard top was bolted in place, significantly stiffening the chassis. The rear suspension was both lightened and strengthened, and everything was stiffened up at both ends. Roll centers and center of gravity were both improved, and the wheels got wider.

A sleeper for the track

John Coombs’ new, technically 1961, now “lightweight” E-type looked and sounded like a production E-type, but was in fact a pure, one-off, bespoke racing car. It was 250 pounds lighter than the original car and 100 pounds lighter than the GTO — with much better power and handling then the standard E-type. The same sleight of hand that allowed Ferrari to race the GTO allowed Jaguar to claim the Lightweight to be a production car. They finally had a car that could compete and win against the GTO.

Jaguar then proceeded to build 11 new “production “ lightweights in 1963, creating a total of 12 cars built.

Particularly in 1963, and to a lesser degree in 1964, the Lightweight Jags made for spectacular racing and achieved a fair degree of success against Ferrari, although bad luck and some fragility limited success in the long championship races such as Le Mans.

1963 also saw the arrival of the AC Cobra and 1964 the introduction of the Ford GT40, so the bar was rapidly being raised as the Ford-Ferrari wars left everyone else behind. The lightweight E-type quickly drifted into competitive irrelevance.

A very special car

Its short competition life did nothing to tarnish the E-type Lightweight’s iconic quality in the racing world. Over the years, the lightweight E has become extremely collectible and frequently replicated (though few have actually re-created the aluminum chassis). What are called “semi-lightweights” (steel chassis replicas) are everywhere in the vintage-racing world, as the remaining 11 “real” cars (one was destroyed at Le Mans) are seldom seen outside of museums.

Our subject car, Number 10, was delivered directly to Australia, where it led a successful — if undistinguished — life. The bad news is that it doesn’t have much history. The good news is that it is relatively unscathed and original, with the result that it is an excellent — but not great — example.

As an unquestioned “crown jewel,” its value has held up well in the recent soft-to-declining market, but it has not appreciated in the past few years.

A somewhat better car sold in early 2015 for a reputed £5 million ($7.6 million), and one of the desirable Cunningham lightweights is reputedly currently selling privately for more than our subject car, so the market seems real and solid, if small. This car sold for a lot of money for an E-type, but it really isn’t one — it’s an English, all-aluminum GTO equivalent. I would say fairly bought and sold. ♦

(Introductory description courtesy of Bonhams.)