SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Vehicle: | 1964 Cooper-Zerex-Oldsmobile “Transformer” Sports Racer |

| Years Produced: | 1961–64 |

| Number Produced: | 1 |

| Chassis Number Location: | Stamped on chassis tube |

| Engine Number Location: | Left front of block |

| Club Info: | Sportscar Vintage Racing Association |

| Website: | http://www.svra.com |

| Alternatives: | 1964 Cooper King Cobra, 1964 Lotus 19/V8, 1964 Chaparral |

This car, Lot 390, sold for $1,037,539 (£911,000), including buyer’s premium, at Bonhams’ Goodwood sale in Chichester, U.K., on September 17, 2022.

On the offhand chance that any of my readers don’t know the analogy of the “Grandfather’s Axe,” I will summarize it here: “Yep, this is my dear grandfather’s axe. It’s had five different handles over the years, and two or three new heads, but it’s still my grandfather’s axe!”

If ever a racing car exemplified the analogy, it is this one. It started out as a 1961 Cooper T-53 grand-prix car, but by the time it got more or less abandoned in Venezuela in the late 1960s, there was virtually nothing even vaguely resembling a Cooper left.

Please note that I am not disparaging the car. It is very real, an extremely important piece of racing development and history, and a worthy project for a McLaren collector. But as presented, it is the vestigial remains of the 1964 McLaren “Jolly Green Giant.” Any associations with the Penske/Mecom Zerex Special are ownership provenance, not material; I doubt that much more than the steering rack remains from the original car.

An unfair advantage

To understand this, we need to dig into the history of this evolving racer. In 1960 Cooper introduced its T-53 “Lowline” GP racer, which used a 1.5-liter Climax FPF engine, and won the world championship with it. For 1961, Cooper sold the T-53A to various private teams and Briggs Cunningham bought one for Walt Hansgen to drive. Hansgen promptly crashed it, bending the frame pretty badly. Afterwards, it was sold as-is to a young driver named Roger Penske. He had the frame rebuilt and the body fixed, then installed a 2.7-liter FPF (they were built as everything from 1.5 to 2.7 liters) to run in U.S. Formula Libre races in 1962.

This was just at the beginning of our domestic professional sports-car racing. Penske saw that some West Coast races in late 1962 had substantial purses for winning, but the races were for 2-seater sports cars. After some discreet inquiries to confirm he would be accepted, he had a full envelope body built on his T-53 with a “meets the rules” second seat mounted in the side pod beside the central driver. He got Zerex sponsorship, painted it red, and entered. This was the beginning of the legendary Penske “unfair advantage,” in that it was really a GP car and far lighter than conventional sports racers, but it met the rules and he won everything.

This, of course, got the rules changed for 1963 to require two equal-size seats within the chassis frame rails. To meet them, Penske had the center section of the chassis cut out and replaced with one wide enough to hold two seats. This design proved to be a poor approach and the resulting car had torsional-flexibility issues that made it difficult to drive. However, it was still very light, and Penske continued to win. The frame was quickly reinforced, which helped more than the added weight hurt. Penske, ever the entrepreneur, sold the car to John Mecom’s team but continued to drive it. It was now blue and white, with a somewhat different body, and retained the Cooper suspension, the FPF engine and a Cooper C5S transaxle.

Another reboot

In the fall of 1963, Mecom and Penske took the car to the U.K. and continued to win, particularly at the Guard’s Trophy race at Brands Hatch. The car remained there that winter, where a young GP driver named Bruce McLaren was thinking about expanding his career to include sports racers.

It was obvious that the 4-cylinder FPF’s time was over. Lotus had introduced the Ford V8-powered Lotus 30, which was beautiful but flat evil in its handling, while Americans were experimenting with putting American V8s into Cooper Monaco and Lotus 19 chassis. McLaren’s problem was that none of those cars were available, while Mecom was eager to sell the Zerex. When Mecom sweetened the deal by including an aluminum Oldsmobile V8, McLaren took the offer.

McLaren drove the now green-and-silver car with the FPF for a few early races, then undertook a complete revamping to fit the Olds engine. Most, if not all, of the frame, suspension and rear bodywork were revised to accept the new 3.5-liter (215-ci) engine and a Colotti transaxle. It was finished in time to ship to the June 1964 Mosport race in Canada, where McLaren won. The car was now known as the “Jolly Green Giant” and continued to race while McLaren and Elva worked to design and build a completely bespoke V8-powered sports racer. That car was the McLaren M1A, which debuted in the fall of 1964.

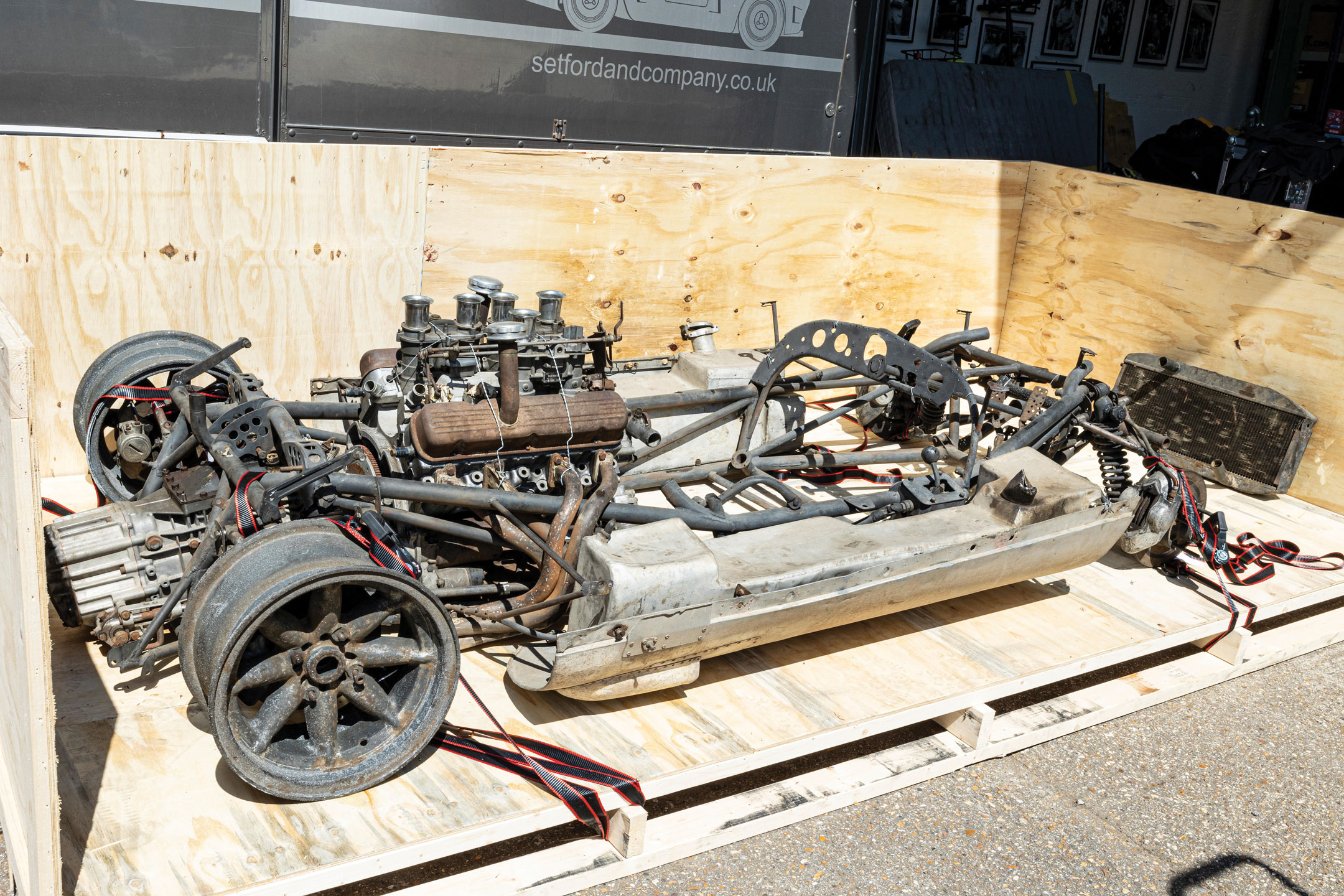

With the arrival of the M1A, our subject car was just surplus. It sold to a Texas racer who ran it sporadically before selling it to Venezuela, where it was used for a number of years before getting stuffed in a corner and forgotten. Nobody seems to know much about the car during this period, but it was a time of radical change in wheels, tires and horsepower. We know the bodywork changed substantially, probably to make room for wider tires. The carcass then sat unattended for over 50 years before being brought to auction.

A “two of one?”

So what are we to make of this sale? The most important thing is to realize that there is virtually nothing on the carcass as purchased that either could or should be saved; it’s all junk. The buyer simply bought the right to spend probably $400,000 to build a new car that can claim the history and provenance of the Cooper/Zerex/McLaren. On top of that, when finished, the new car will be revered but completely uncompetitive. It came at the beginning of a radical change in sports-car design that was immediately superseded by more advanced designs. Even by late 1964, the car was completely outdated.

From a collector’s standpoint, however, this is a hugely important car, and well worth re-creating because of its centrality to the development of the modern sports racer. It marks the tipping point where serious horsepower first got used in a mid-engine chassis. This is where McLaren’s cars all began.

An American collector found the frame parts, drawings and other bits of the early Penske Zerex. He used a Cooper T-53 frame and worked with the original Penske mechanics to re-create the center-seat version of the Special. Our subject car, when finished, will carry the history of the 2-seat version. It is impossible for either car to be “original” or “real,” they will both be re-creations with legitimate associations to a now lost but famous racer.

I don’t know who bought the project, but I assume it will become an honored anchor to a serious collection of McLaren racers. It will certainly deserve the role. It sold for a lot of money, and as I am not privy to the logic of the purchase, I cannot question it. Some astute collector decided it was worth the commitment and the market has spoken. Well sold. ♦

(Introductory description courtesy of Bonhams.)