SCM Analysis

Detailing

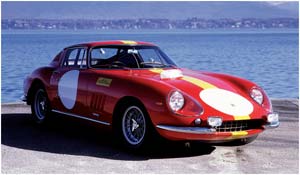

| Vehicle: | 1966 Ferrari 275 GTB/C |

| Years Produced: | 1966 |

| Number Produced: | 12 |

| Original List Price: | approx. $10,000 |

| SCM Valuation: | $650-850,000 |

| Tune Up Cost: | $2-3,000 |

| Distributor Caps: | $200 |

| Chassis Number Location: | stamped on chassis near right front upper wishbone anchorage |

| Engine Number Location: | right side of engine block above starter motor boss |

| Club Info: | Ferrari Owners Club, 8642 Cleta Street, Downey, CA 90241; Ferrari Club of America, 15812 Radwick Silver Springs, MD 20906 |

| Website: | http://www.ferrariownersclub.org |

| Alternatives: | Ferrari 330 LMB, Jaguar Lightweight XKE |

This 1966 Ferrari sold for $1,080,061, including buyer’s premium, at Bonhams’ Monaco auction, held on May 15, 2004.

The GTB/C is the ultimate 275 GTB, a true purpose-built race car that can’t really be compared to its production siblings. In many ways it can claim to be the rightful successor to Ferrari’s 250 GTO. Indeed, the 275 GTB/C is faster and more technically advanced than the GTO. It is also rarer, with only 12 produced versus 37 GTOs. Why then is a 275 GTB/C worth just a fraction of the GTO’s $7.5-$9 million value?

Blame the FIA. In the early 1960s, the rules for homologation of production GT race cars clearly specified a minimum production of 100 cars. Ferrari got the GTO approved by promising to build 100, then very publicly spanked the FIA by fielding a wildly successful purebred racing car, with no intention of meeting the production requirements. And so, having been thoroughly burned, the FIA wasn’t very inclined to be agreeable when it came time to produce a successor. It simply refused to homologate the 250 LM (the intended successor) as a production GT car.

Ferrari was thus forced to produce a competition version of the 275 GTB in order to fight the production GT battles, and it really needed to look and feel enough like the street version to get it past the authorities. Typically for Ferrari, it took three attempts before they pulled it off.

Act 1: Ferrari built four pure racing cars, often referred to as the “GTO 65.” These were super-lightweight, tube-framed specials with 250 LM engines and bodywork that sorta looked like a 275 GTB. But the FIA said, “Nope,” and Ferrari threatened to abandon GT Championship racing. Close curtain.

Act 2: Ferrari produced a series of 10 more-or-less production short-nose GTBs, but modified for competition use. They had aluminum bodywork, outside filler caps, and six carbs, but little more, and Ferrari decided they weren’t fast enough for factory competition. Close curtain.

Act 3: Finally, Ferrari built the 12-car run of the 275 GTB/C. (The others were not given this moniker.) These were the last competition GT cars designed and built from the ground up by Forghieri and the racing department at Maranello. (Later Daytonas were production cars modified in Modena.) The FIA approved. Applause.

Though they look a lot like a standard long-nose GTB (they’re not identical) these are serious racing cars. The frame architecture is the same as production 275s but it’s a special frame. The engine is a three-carburetor version of the 250 LM engine (the three carbs, rather than the expected six, were due to a clerical error in the FIA filing), with a 22-quart dry sump, turning out 280 hp at 7,500 rpm. Ferrari used electron castings (magnesium alloy) all over the place to save weight, including the transaxle case. The result is a car that weighs 500 pounds less than a steel-bodied 4-cam. The bodywork is nothing more than painted aluminum foil (half the thickness of production GTB aluminum bodywork) and dents if you look at it wrong.

The GTB/C is also the last competition Ferrari to run wire wheels, specially built Borranis, and for good reason, as the wheels couldn’t handle the grip of the new M Section Dunlops and often broke. Ironically, the two GTB/Cs sold for street use were given stronger alloy wheels.

The interior of the car was complete and looks like that of the GTB/4 (though it’s much lighter) and the engine is docile enough to idle, so it’s easy to forget that this is a serious piece of kit. A GTB/C will easily walk away from street Daytonas or Boxers once you get it up on the cams.

Oh, yeah, the cams. Dyke Ridgley wrote a piece in Cavallino where he described the performance thusly: “What are these cars like to drive? Up to 2,500 rpm it is buck, buck, cough, cough, spit, spit. Between 2,500 and 4,000 the engine is smooth but weak-kneed. Above 4,000 you get the feeling that the car may really go after all, and at 5,000, the GTB/C tries to throw you out the back window!”

The problem is that your buddies down at the golf club are still going to think you’ve got a GTB, and one with lumpy bodywork to boot. That seems to be what keeps these at the lowest market price of any pure-racer Ferrari of the ’60s. Of course, to look at it another way, it’s a great value. And while 275 GTB/Cs have been stuck in the million to million-and-a-half range for years, I have to think that the chances of the world waking up and giving these cars a much higher value is far more likely than their values going down. Which is to say, this purchase was a very safe investment in a very special car.