SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Vehicle: | 1972 Matra MS 670 |

| Years Produced: | 1972 |

| Number Produced: | 3 |

| Chassis Number Location: | Tag on monocoque |

| Club Info: | Matra Enthusiasts Club U.K. |

| Website: | http://www.matra-club.net |

| Alternatives: | 1968–71 Porsche 908, 1972 Lola T-280, 1969–72 Alfa Romeo 33 TT 3 |

This car, Lot 5, sold for $8,276,898 (€ 6,907,200), including buyer’s premium, at Artcurial’s Parisienne sale in Paris, France, on February 5, 2021.

The French are a proud nationality. With an appropriate nod to Gottlieb Daimler in Germany, France invented and led development of the automobile. France invented motor racing and completely dominated the early years. France created and promoted what is easily the most important motor race in history: the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Yet as of the spring of 1972, France had been completely shut out from even coming close to winning that race for 21 years. Does this sound like a recipe for frustration?

Rule changes

Yes, there was a lot of national pressure for France to re-enter the winner’s circle in international racing, but there was a problem in that its auto industry was concentrated on small-displacement utilitarian cars (also a few luxury Citroëns), so the technical base for racing success just wasn’t there. In 1964, the newly appointed chief of Matra, an armaments and aerospace company, had picked up the mantle of responsibility and predicted both Formula One and Le Mans mastery within 10 years.

Devoting the not-insubstantial resources of Matra to the project, it managed to win the Formula One championship in 1969 (admittedly with Ford Cosworth power and a Hewland transaxle, but only Ferrari and BRM used anything else). Le Mans, as the ultimate 24-hour test of endurance, was more of a challenge. Through much of the 1960s the front of the finishing order had been a titanic struggle between Ford and Ferrari with little chance for the lesser manufacturers, but for 1968 the rules were changed to improve the opportunities.

The rules for international auto racing are set by the FIA, which is based in Paris. Though officially a purely international organization, they are not immune to nationalist pressure. At any rate, for the 1968 season the rules changed to allow a maximum 3-liter displacement for the premier “Prototype” class, ostensibly to promote safety but more transparently trying to end the Ford and Ferrari dominance. They were worried that the new rules would limit the size of the entry lists, so they put in a few loopholes for 1968–71 to ensure enough entrants. Ford drove the GT40 and Mirage variant through one of the loopholes while Porsche drove the 917 through another (followed by Ferrari’s 512) and the championship remained a horsepower playground through 1971.

Matra had developed its own 3-liter V12 in anticipation of the 1968 season, selected both as an excellent endurance-racing configuration and because of the signature sound. Firing order, porting, and exhaust design were specifically chosen to give it a characteristic “shriek” at speed. It took a few years to figure it out, but this was just as well, as Porsche owned top-tier racing through 1971. By 1972, Matra had its cars well developed and ready to go.

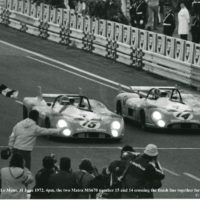

The auguries were favorable for Le Mans 1972. Ferrari’s 312PB was really a Formula One car with fenders, so unlikely to survive 24 hours that the factory didn’t even enter any, leaving Porsche’s somewhat ageing 908, Alfa Romeo’s fragile Tipo 33 TT 3 and Lola’s T-280 as Matra’s primary rivals. After a long and eventful race, Henri Pescarolo and Graham Hill brought our subject car to the checker, the first French car to win Le Mans since 1950.

A national treasure

Every Le Mans winner is an icon by definition: The sobriquet alone doubles or triples the market value of any car that carries it. On top of that, this car is a national treasure. The story of how it left the Matra Museum and ended up at public auction is more suited to screenwriters than a journalist like me, but it happened.

Originality is always an issue with old racing cars, a problem compounded for cars after about 1970. Cars that in the earlier days were built and raced as complete assemblies became collections of components that were commonly intermixed over the course of races or years, and this car was no exception.

After Le Mans, this monocoque chassis raced with a variety of engines, transaxles, rear suspensions and bodies before being consigned to “show-car” status at the end of 1973. As such, it got an empty shell engine, Porsche transaxle case and 1973 bodywork. The real bits had moved to different cars. Though recommissioned for sale and fully operational, little but the chassis itself actually ran at Le Mans in 1972.

Value not added

Another issue with the sale was the tax situation. Since the car had never been sold, 20% VAT was due on the entire price if the car stayed in the E.U., which is a substantial addition. I am told that the car went to the U.K., which because of Brexit is now outside the system. European bidders had to have been limited by the tax liability.

While $8.3 million may seem like a ton of money, for a Le Mans winner it is really pretty cheap. I expect that the relative obscurity of the manufacturer (it’s not a Porsche or Ferrari) plus the lack of original components affected the bidding. The rumor is that it went to a serious Matra collector who may have access to most if not all of the original pieces. If so, a complete, correct and far more valuable 1972 Le Mans winner can be reassembled. This was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and the buyer made an astute purchase. ♦

(Introductory description courtesy of Artcurial.)