The Lancia Stratos is unquestionably the most extraordinary rally car ever produced. It is also one of the most successful, having won the World Rally Championship three times (and probably would have continued if allowed to do so).

The first prototype Stratos was a project designed by Marcello Gandini for Bertone and exhibited at Turin in 1970. It was essentially an exercise in extreme style and very impressive, with the overall height at just 37.4 inches. This strange, wedge-shaped prototype attracted the attention of Cesare Fiorio, the legendary boss of the competition department of Lancia, who needed to replace the carmaker’s aging and outdated Fulvia coupe. Gandini reinvented the design into a relatively more usable car, slightly taller, but still very radical compared with production cars of the period. The lack of overhangs, the long flat hood, the compact silhouette and the huge wraparound windshield all combined to a shape like nothing else known until then.

Lucky for Lancia, Ferrari had recently become a part of the Fiat Group, so the mechanicals of the Stratos came from the Prancing Horse brand. The 2.4-liter V6 engine from the Dino became the natural choice, as it was a well-tested, compact and powerful unit, which had already proven itself in the Dino 246 GT and also in the Fiat Dino coupes and convertibles.

The car still needed to be developed, and for that another talented engineer — Gianpaolo Dallara — was involved. After a few pre-production cars in 1973, the Stratos was made in sufficient numbers in 1974 to allow homologation into Group 4. The total production was eventually about 495 cars. Of these, Lancia used 10 to make official factory Group 4 cars, the others being sold as “stradales” or street cars, some of which were prepared by private rallyists for rallying, following the approved Group 4 regulations.

Unlike many rally cars, the Stratos was not derived from a regular production car, but was a clean-sheet design specifically for competition purposes. Its radical design gave it diabolical handling, and combined with a very flexible and powerful engine, the Stratos remained a very competitive car for years after, intimidating all competition.

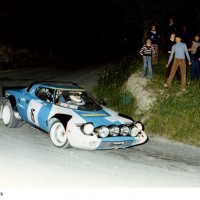

Manufactured by Bertone on October 31, 1974, and bearing chassis number 391, the Lancia Stratos on offer here went to Lancia Spa. Painted a Blue Azzuro, the car was prepared in a workshop to compete in the Italian rally championship. Thanks to the research of Thomas Popper, we know that between 1978 and 1980, this particular car participated in at least 10 rallies. It is obviously eligible for many historic events in which the spectators are bound to greet the car with all the fervor for a real legend of the motorsport.

SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Vehicle: | 1974 Lancia Stratos Groupe 4 |

| Number Produced: | 495 |

| Original List Price: | $17,000 |

| Engine Number Location: | On block above water pump |

| Club Info: | American Lancia Club |

| Website: | http://www.americanlanciaclub.com |

This car, Lot 127, sold for $456,984, including buyer’s premium, at the Artcurial Paris auction on November 11, 2012.

Think about it: Have you ever seen a photo of a Lancia Stratos in motion where it wasn’t sideways? I don’t think I ever have, either, and I suggest that this tells us something.

From looks to performance to handling characteristics, there is nothing about the Stratos that is normal, rational or arguably even sane, but they’ve got exuberance and excitement packaged like few other cars of the past 50 years. Dull, they weren’t. Neither were they comfortable or remotely practical, but that wasn’t the intent; the Stratos was conceived to be both the ultimate rally car of its time and an outrageous visual statement to define Lancia to the world in the anything-goes years of the early ’70s.

Its success on both fronts has made the car iconic.

A scary, great, cool car

I’ll need to set the stage to explain how it all worked. Lancia was one of the oldest and most venerable of Italian auto manufacturers, and in the early post-World War II years, they created a niche as a supplier of high-quality, high-performance and relatively expensive small-displacement road cars.

As you can imagine, this was a small market niche even in Europe — and completely unsuited to the American market. In Europe, however, they were ferocious competitors on the rally circuits and developed a very devoted customer base. Unfortunately, the 1960s were not kind to niche marketers, and in 1969, both Lancia and Ferrari found themselves absorbed into Fiat (with Abarth to follow in 1971).

Becoming part of the Fiat empire was a shock, but Lancia pushed ahead regardless. They were looking to replace the aging 1.6-liter Fulvia HF and were working with Bertone to build a very short run of purpose-built rally racers based on the Stratos concept car. Then the FIA folks tossed in a monkey wrench that required a 500-car production to qualify for the Manufacturer’s Rally Championship. This meant that if Lancia were to continue with the concept, they would have to build a “homologation special.” Bertone was willing and able to build the basic shells, but they had to come up with a suitable engine and Fiat’s approval. After several years (1971–73) of Italian high-opera machinations, Fiat bought off on the idea, Ferrari agreed to extend the production of their 246 engine by 500 units (the 246 Dino ended production in 1974), so that it could be used in the Stratos, and Lancia was clear to start building cars. Production was in 1974 and 1975. Because of safety and emissions issues, none were imported into the U.S.

Made to race — and win

The execution of a “homologation special” can have a number of different results depending on the circumstance: Ford made a serious effort to produce and market a street version of their GT40 that was actually civilized. Lancia, on the other hand, made few adaptations to create the “Stradale” production version of the Stratos — probably under the assumption that they were all going to be turned into rally cars anyway.

The result was that the Stratos was somewhere between scary and suicidal for an unprepared driver. Much of this was essential in the design of the car: The suspension was designed around race tires, not street rubber, the wheelbase is only six inches longer than a Mini Minor while the track is four inches wider than a BMW 2002, and 63% of the weight is on the rear wheels.

Combine this with about 200 horsepower in the Stradale (280 or so in the race-prepared cars) and a weight just over 2,000 pounds, and you have a recipe for SUDDEN!

There is a reason all of the photographs show them sideways; it could be steering input, power, brakes, or even an unexpected manhole cover near the apex, but there it goes. Also, with the almost-square layout, once it starts to go it takes a very quick driver to catch it. As evidence, a friend of mine was almost killed during a demonstration ride on a residential street a few years back (the car was destroyed).

This is made more difficult by the interior layout. Although it is a very wide car, the narrow roofline jams the driver and navigator so close together in the center that they almost have to touch shoulders to fit in, which can be a problem when things get busy.

The cockpit is hot, noisy, and strangely claustrophobic in spite of the huge windshield. Stradale or not, the Stratos, my friend, is a serious racing car. Don’t get me wrong, though: I love them — these cars are SO COOL! There is nothing else from the mid-1970s that even comes close for sheer in-your-face outrageousness. The Stratos only came in five colors — all neon.

At the end of the day, adjectives such as “cool,” “outrageous,” “wildly successful,” “fast,” and “rare” always outweigh comfortable, safe, or practical when it comes to collectibility. The subject car is one of the best examples — it is not a factory team car, but it was a real racer from the beginning, and apparently well documented as such. And good ones are tough to find. Not surprisingly, a lot of them got written off in the era.

To a man, my European rally-car friends were drooling over this car and wishing they had the money to own it when it came available, even though they’d be afraid to drive it much. It’s that kind of car, and at the money, I’d say fairly bought. ?

(Introductory description courtesy of Artcurial).