SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Vehicle: | 1985 Porsche 959 Paris-Dakar |

| Years Produced: | 1985 |

| Number Produced: | 3 |

| Original List Price: | N/A |

| SCM Valuation: | $5,945,000 (this car) |

| Chassis Number Location: | On bulkhead just aft of gas tank |

| Engine Number Location: | On fan housing support, right side |

| Club Info: | Porsche Club of America |

| Website: | http://www.pca.org |

| Alternatives: | 1985 Lancia Delta S4, 1985 Audi Sport Quattro, 1985 Peugeot 205 Turbo 16 |

| Investment Grade: | A |

This car, Lot 196, sold for $5,945,000, including buyer’s premium, at RM Sotheby’s Porsche 70th Anniversary auction in Atlanta, GA, on October 27, 2018.

There is an old saying, “Old men and fools predict weather in the mountains,” and the same seems to apply to auction results.

Most SCM readers are very aware that the collector-car market crested a few years ago and has been in a general, gentle decline since then. However, this trend is anything but comprehensive: Every once in a while, a sale comes along that defies conventional logic.

Last month, I wrote about an Elva Mk I sports racer that inexplicably sold for at least twice what any rational observer would have predicted (January 2019, Race Profile, p. 82), and today I get to try to explain why at least two people at an auction decided that a Porsche 959 Group B rally car is worth close to $6 million.

I don’t know the names of the successful bidder or the underbidder. My information sources also are in the dark on this, so I will have to work from what we do know.

Blowing away the estimate

To start with, the pre-sale estimate was $3 million–$3.4 million, so that is what RM Sotheby’s was hoping for. Two knowledgeable Porsche brokers and a specialist for a different auction company all agreed that the car was $3 million on a very good day, which provides corroboration.

But our subject car sold for almost twice that.

The sale price is way too big to blame on the proverbial dentist from Tulsa who got carried away at the bidder’s bar. Somebody made what he or she saw as a rational decision. The question is, what did we miss?

Three possible factors

I suggest that we consider three basic factors: the car, the livery and the possibly special nature of the Porsche market. We’ll start with the car itself.

The 1980s were a very good time for Porsche. They were selling road cars like crazy and were so dominant in both international and American road racing that Porsches filled well over half of every starting grid.

In going from strength to strength, Porsche decided to challenge Ferrari and Lamborghini in the emerging ultra-performance supercar market.

So the 959 project began.

For reasons of continuity, marketing and possibly, corporate ego, the car needed to maintain the mechanical layout and some visual similarity to the 911, but it would need all-wheel drive and state-of-the-art electronically controlled suspension.

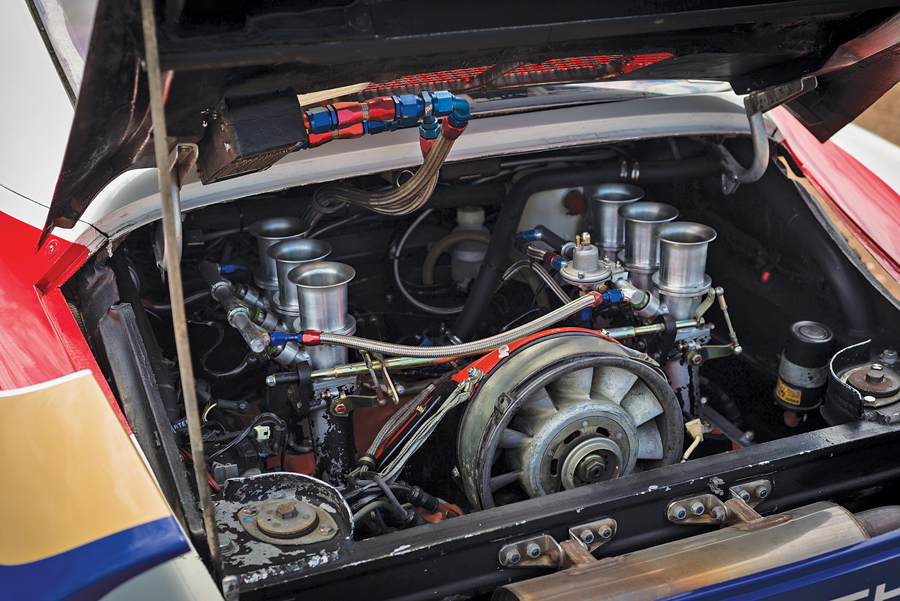

Porsche already had plenty of engine in the competition-proven 935 unit — although more sophisticated dual-stage turbocharging would make street drivability more appropriate without sacrificing horsepower. As a road supercar, it, of course, had a luxurious interior, air conditioning and appropriate creature comforts included. A pure track-racing variant was envisioned, to be called the 961.

Porsche had little interest in off-road “adventure” rallies such as Paris-Dakar, as their earlier efforts on the East Africa rally had been unrewarding at best. However, Jacky Ickx, their star driver in FIA endurance racing and core of the important Rothmans sponsorship package, was a difficult man to ignore.

Ickx drove a Mercedes G-Wagen in the 1983 Paris-Dakar rally and had enjoyed himself immensely, so he approached Porsche about entering their all-wheel-drive 959 for the 1984 event. After initial reluctance, Porsche agreed to field a three-car team with Rothmans sponsorship and Ickx managing.

The 959 itself was inappropriate, so Porsche took 911 SC shells and put 959 drivetrains with jacked-up suspension and normally aspirated engines into them to create what was called the 953. It proved to be the correct weapon for the battle, and Porsche won overall — with all three entries finishing.

Let’s do it again

This led to considerable corporate enthusiasm for the 1985 event, and the three cars entered had evolved toward the 959 both mechanically and visually — although they were still based on the 911 SC chassis.

The all-wheel drive was far more advanced, now with electronic control of the front-rear torque split, and the suspension was more rugged and even higher off the ground. The engine remained normally aspirated in respect to reliability and the lousy gas available in Africa.

The bodies now looked like 959s, complete with the distinctive rear-wing treatment. It was not a good year, with two cars crashing out and the third (our subject car) running out of oil pressure with a broken oil line. Porsche entered again in 1986 with a true 959 variant and won, after which they dropped back out of adventure rallying.

A factory racer and an important development

Our subject Paris-Dakar 959 is thus a very special car, both a purpose-built “factory team” racer and one of three (of five remaining) privately owned examples of an important, if short-lived, part of Porsche racing history.

Unless you have a 20,000-acre ranch and the willingness to risk large quantities of money, there is little chance of ever seriously driving it, but if you want to own one, this was likely the only available opportunity.

What’s on the car matters

In terms of collectibility, livery deserves our consideration.

Particularly with racing Porsches, color can matter because it conjures associations with the great teams of each era. For the 917s of the early 1970s, the blue and orange of the Gulf Wyer racing team implies greatness that can add 20%–40% to the value of a car. The same is true of Rothmans livery for the Porsche racers of the 1980s. Admittedly, all Paris-Dakar Porsches carried Rothmans colors, but the point remains.

I’m not sure that we are any closer to working out why this car sold for several million more than the experts were predicting, but we may be on the right track.

The Porsche market speaks loudly

I have frequently noted that even in today’s soft market, the “crown jewels” have continued to sell very well. A reasonable question is whether this car was a crown jewel. The term generally refers to exquisitely rare, important, beautiful and generally unavailable collection cornerstones, the kind of asset that signifies membership in various ultimately exclusive socio/cultural strata.

Ferrari GTOs and TRs are obvious examples, as are Porsche 917s (ideally blue) and various Maserati, Jaguar and Aston Martin racers. But a production-based Porsche?

An answer may be that obsessive Porsche collectors are a group unto themselves, and a Rothmans-liveried factory-team rally car from the glory years of the 1980s may well have been seen by several wealthy collectors as an essential — but almost unattainable — puzzle piece for the ultimate Porsche collection.

With only one other 1985 959 and one 1984 953 in private hands, the chances of another becoming available are extremely small. So if someone wanted it, the choice was to step up or step away.

I suggest that this car was very well sold — but it was probably a rational purchase nonetheless. ♦

(Introductory description courtesy of RM Sotheby’s.)