SCM Analysis

Detailing

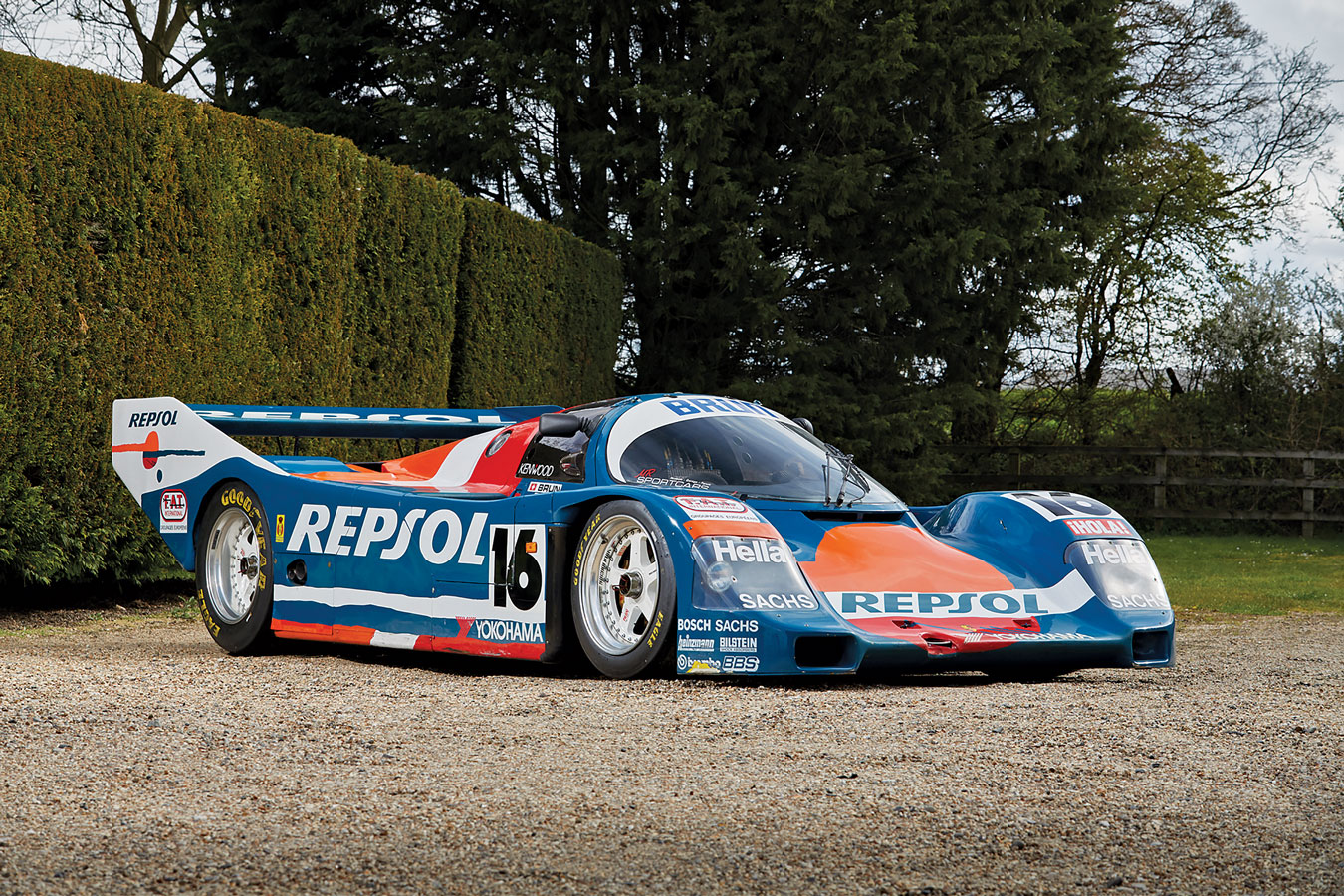

| Vehicle: | 1990 Porsche 962C |

| Years Produced: | 1984–90 |

| Number Produced: | 56 (about 35 non-Porsche chassis) |

| Chassis Number Location: | Inside cockpit on rear bulkhead |

| Engine Number Location: | Fan housing support, right side |

| Club Info: | Porsche Club of America |

| Website: | http://www.pca.org |

| Alternatives: | 1990 Jaguar XJR-12, 1990 Nissan R90CP, 1985–90 Spice Cosworth |

This car, Lot 14, sold for $1,052,700 (£759,000), including buyer’s premium, at the Gooding & Company Geared Online auction on June 18, 2021.

The market values for any race car built in a substantial production run will vary from car to car, but there are few others with the range of the Porsche 956/962 racers. The double-Le Mans-winning 956 (1984 and 1985) sold for over $13 million a few years back. The 1983 winner topped $10m (SCM# 266280). Our subject 962C, however, made just $1.1 million. Though not identical, these are extremely equivalent cars. Parsing out what has that much impact on value is our theme today.

Rule changes

As so often happens, the whole thing started when the FIA changed the racing rules to a new formula starting in 1982. Instead of specifying engine size or the like, it specified how much fuel a car could carry and how frequently it could stop for more. This effectively meant that a car had to get at least 4.5 mpg while racing flat out, so “fuel economy” was relative, but it had a real impact on design.

Porsche’s response was to create the 956, which was a huge departure from earlier designs. It used Porsche’s first aluminum monocoque chassis and was its first car with “ground effects,” tunnels in the floor pan to generate downforce (along with wings). For power, the engineers chose a 2.6-liter flat 6 with four cams, four valves per cylinder, twin ignition, water-cooled heads and two turbochargers. To keep the wheelbase optimally short and the weight centered in the car, the driver’s feet ended up almost six inches in front of the front wheel centerline. To save weight, the roll cage was aluminum.

The Porsche 956 immediately proved dominant in International FIA class C racing, sweeping the podium at Le Mans in 1982 and continuing to be the 800-pound gorilla for years to come. Porsche both ran a factory racing effort and sold cars to private teams, eventually withdrawing the team involvement in favor of simply selling racers.

Coming to America

The complication was that the 956 didn’t fit the American IMSA rules, and the U.S. market was wildly important, for both racing-car sales and marketing road cars. The big problems were that IMSA required a steel roll cage and that the driver’s toes must be behind the front axle plane. The engine, too, was an issue, allowed only two valves per cylinder and a single turbocharger.

Porsche thus created the 962 to meet IMSA rules. The wheelbase was stretched six inches to get the driver’s footbox behind the axle plane, and the air-cooled 3.2-liter 935 engine was used with a single, huge turbocharger. Visually the 962 stands out because Porsche effectively just moved the front wheels six inches forward. Overall body length remained unchanged from the 956, so the nose is more abrupt, with a big bump in the back over the turbo.

The 962 proved every bit as successful in U.S. racing as the 956 had in FIA class C, and Porsche was happy to sell as many as racers wanted to buy, so for years the front of the IMSA grids were almost all Porsche.

Development continues

The idea of having the driver’s tootsies way out front was unsafe, as was the aluminum roll cage, so for 1985 the FIA adopted new safety rules to fix things. At that point, Porsche created the 962C for international racing by installing the Group C engine package. Bosch developed digital Motronic engine-management systems that improved fuel use, so over the next seasons the engines got a bit larger and gained water cooling on the cylinders as well as the heads (called the “water water” engines, which were more powerful).

As the 1980s progressed, both Mercedes and Jaguar entered the fray, and provided Porsche with plenty of serious competition, but the 962s continued to be developed. They remained in the hunt, if not the dominant force they had been at the start. The last year for the 962C as a Porsche-built racer was 1990 (although independents continued to build and race them), and it was a significant improvement over 1989: 2.5 seconds a lap faster at the Nürburgring, but the model was clearly at the end of its career.

Not uncommon

Porsche itself built 56 total 962s, 15 for the factory team and 41 sold to privateers. Something like 35 independent chassis got built and run, so there are a lot of them around.

The primary considerations in valuing old 962s are history, livery, weapons-grade usability, and authenticity, more or less in that order (though they are frequently intertwined). As probably the most dominant endurance racing car for at least eight years, some cars have spectacular racing résumés, and that is the primary determinant (a Le Mans win is worth at least $10m). Factory team livery (mostly Rothmans) is another huge factor for collectors, since it correlates to importance.

Once you step past the museum-quality collector examples, the value drops pretty fast, and being a good vintage racer becomes important. These are complicated and very fast cars, so having a car truly track-ready is extremely important. If it’s not, you can be looking at a pile of money to get it ready.

Authenticity is a jumbled issue with these cars and has mostly to do with the monocoque tub. It was Porsche’s first effort and proved to be not as stiff and resilient as it might have been, with the result that a number of companies built stronger, stiffer ones over the life of the 962. Porsche was fine with this, and, in fact, bought some to use in its own cars as well as selling components to build complete cars around the new tubs. Which is better? It sort of depends on what you are looking for.

Last and best

Our subject car is from 1990, a plus in that it is the last and best from the factory. It is completely original and unmessed-with, reference-correct, and has the late-production four-valve “water water” Group C engine. The downside is that it has effectively zero history (two DNFs with a minor team), so there’s little collector value. It hasn’t run in something like 25 years, which means that making it competitive will cost at least $300k. Since it is in the post-Brexit U.K., importing it to Europe will cost about 7% (or 2.5% to the U.S.) and you are looking at a daunting purchase decision.

The result is an interesting and original but not particularly valuable car, a minor collectible that is barely worth the expense to make it a racer. My guess is that it will continue as a static display in somebody’s collection. As such, it was fairly bought. ♦

(Introductory description courtesy of Gooding & Company.)